The Clergy and the Lay People – The Readers and the Listeners

to describe what were the tasks and the role of the clergy in the Middle Ages;

to define what were the social groups and occupations that the townsfolk fell into;

to describe what were the origins of the knight and magnate classes;

to explain why it was virtually impossible to change one’s class (standing) in the Middle Ages.

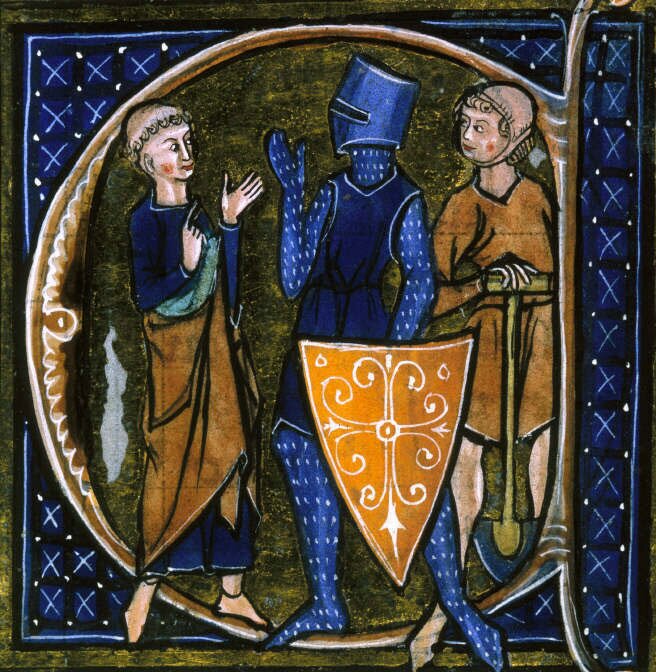

In the Middle Ages, much like in the present times, there existed various groups that members of society fell into, and the various roles they entailed. The shaping of the social classes brought about a very clear division of the Medieval society that would last for centuries to come. On the one hand, it assigned certain roles, rights, and obligations to each of the groups, but, on the other, it made leaving the social class of one’s birth very difficult. The members of the classes were not uniform, either. There existed many divisions and differences between them. Sources indicate that the warriors, knights and magnates played the first fiddle. They were the ones that shaped the Medieval state and played decisive roles in politics, and, in addition, fronted the heftiest sums for the development of arts and culture. They placed great emphasis on family tradition, and, in later centuries, on Christianity and its defense (“the Christian knight” – “miles Christianus”). The unwavering base of the knightly virtue was the loyalty towards one’s lord, then, later, also towards God and the Church. The warrior became a man of God, and the sword – the expression of divine will. The image of the stern, divine warrior began to change at the turn of the twelfth century, when the existing virile virtues were joined by the love of beauty and noble damsels, as well as the ability to understand and enjoy arts and culture.

The second fiddle was played by the people of the Chuch and God. In those times, they constituted the intellectual elite of society; they were responsible for safeguarding and relaying the memory of the European culture and tradition. This was rendered possible owing to, above all, operating on the same, unchanging rules, the same culture, and based on one, unchanging language – Latin. The care for memory and culture, however, was not the most important task of the people of the Church, even though they constituted pillars of both. Their main objective was to ensure that the Christians were under sacerdotal care, as well as to preach the Word of God to those that did not know it. They believed that this way they were implementing the advice of Christ himself, bringing the people to the highest form of good, and ensuring them eternal life.

The final group to be discussed was made up of the townsfolk. This one had many layers and divisions. Using the material status of its members, one can distinguish the patricianspatricians – the most wealthy ones who possessed all of the political power; the commonerscommoners, or the majority of the townsfolk and the towns’ general population; and the plebeiansplebeians – the town’s poorest that had few rights and little money. Belonging to either of the groups determined one’s degree of participation in the town’s political life. What united the townsfolk, rich and poor alike, were the temples. They had “better” and “worse” spots inside them, but the townsfolk prayed for their towns’ prosperity together. At the same time, the relations between the Church and the townsfolk were complicated. On the one hand, the bishops were often the caretakers and managers of entire communities. On the other, many towns where money reigned supreme would become centers of sin and witness many turn their backs on God. Owing to the development of trade and convenient geographical situation, the cities of Italy and the Netherlands became the richest, with time rendering their surroundings dependent on them and becoming independent states. They became the symbol of the townsfolk’s freedom from duties towards the aristocracy, the knights, and the clergy.

Reading the text below, pay attention to whether the triple division was the only social division according to Adalberon. Where did he see its strengths?

In the text by Bishop Adalberon mark the fragments that continue the sentences below.

The people are divided into the lords who live off the work of others, and their servants. The three classes support each other, maintaining the balance of the world. The society is divided into clergymen, knights, and servants.

The King: Is the entirety of the House (People) of God subject to one law?

Clergyman: The order of faith is simple, yet the nature of society is triple.

The law of man indicates two states:

nobles and servants, [who] are not subject to the same law.

Among the two, there are two [kinds]: one governs, the other one orders.

It is thought that, owing to their advice, society is stable.

Then there are those who are not limited by any authority. [...]

They are warriors, protectors of the churches

they defend all of the people, rich and simple,

and, thusly, themselves as well.

The destiny of the servants is different:

those people have nothing but care.

Who could count, using an abacus,

their care and efforts, those immense endeavors?

The Royal Treasury, the opulent garments, everything feeds off the servants.

No free inhabitant of the kingdom could possibly survive without the servants [...]

The lord is fed by the servant, whom he hoped to feed himself.

There is no end to the servants’ tears.

Triple is thus the House of God, thought of as uniform:

those pray, the others fight, and, finally, the others work.

Those three classes coexist and do not suffer due to conflicts,

as the duties of one serve the two others [...]

For the triple unity of society is simple.

Thus the law prevails, and the world thrives in peace.

Read the words of the 11th‑century oath sworn by the members of the “Peace of GodPeace of God” movement in Germany. Afterwards, complete the exercise.

Source texts of the Middle Ages

From Christmas until the first Monday after Epiphany, then from the Great Lent until the octave of the Green Week, then on all of the holidays and their eves, and for three days of every week, that is from Thursday evening until dawn on Monday, may peace rule everywhere, and may no one strike his enemy.

Whoever kills during that time, may he be sentenced to death. Whoever inflicts wounds, may he lose his hand. Whoever strikes another with a dagger, if he has been born into a noble family, may he pay a fine of a pound of silver; if he is free or a ministerialis – 10 solidus, and if he is a subject, may he receive a punishment to the skin and the hair (i.e. by being whipped and receiving a forced, humiliating haircut).

May every house and court [...] enjoy perpetual peace as well [apart from the days indicated in point 1]. May nobody intrude upon the premises, break inside, or invade them violently. Whoever should dare to do it shall receive capital punishment, no matter where he comes from.

Should one fleeing an enemy enter his own house or that belonging to someone else, may he be safe there. Whoever should cast a spear or another weapon after him inside the premises – may he lose his hand.

Source: Source texts of the Middle Ages, red. Józef Garbacik, Krystyna Pieradzka, Kraków 1978.

Sort the breaches of peace, starting from those considered the most grave.

- House invasion.

- Killing during peacetime.

- Attack on a person taking refuge in a home.

- Wounding somebody during peacetime.

Mark the rules concerning the Order of Friars Minor (the Franciscan Order)

rules

The rule and the life of Friars Minor depends on the staying faithful to the Holy Gospel of our Lord, Jesus Christ, by living in obedience, with no property, and in chastity .

They strictly order all of the friars not to accept any money or anything of monetary value, neither directly nor through others.

Those friars who have been granted the grace of ability to work, may they work diligently and piously, so that they may avoid laziness, the enemy of the soul, and not quell the spirit of holy prayer and piety, which should be catered to by all of the earthly affairs. As reward for their work, they may accept items necessary for their survival, except for money and anything of monetary value. May they accept them with humility, as appropriate for the servants of God and preachers of holy poverty.

The friars shall not make any property purchases: neither homes, nor land, nor anything else. And as pilgirims and guests [...] to this world, serving the Lord in humility and poverty, may they ask for alms faithfully; they should do so without shame, for Lord rendered himself poor for our sake in this world. [...]

Study the interactive illustration and learn more about the inhabitants of the Medieval town.

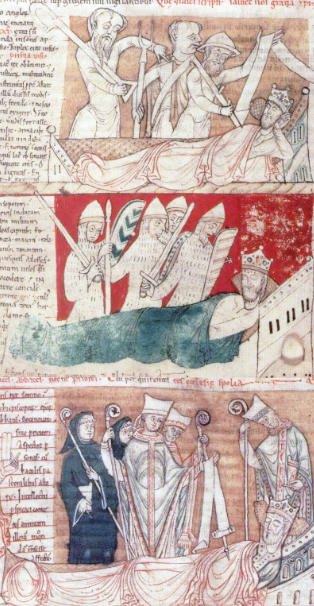

According to the English chronicler John of Worcester, King Henry I once experienced terrible nightmares. In those nightmares, his subjects attempted to gnaw upon him, cut up the body, and batter him using his insignia. All of it – as the chronicler would explain later – was to be punishment for the King’s misdeeds.

Look at the twelfth‑century illustration depicting those dreams. Mark the social groups that the English society was divided into. Are the tools and symbols held by the members of the groups suggestive of particular contribution of any of the groups in the creation of the culture?

Drag and drop the elements in the appropriate places.

clergy, knights, peasants

Keywords

clergy, patricians, plebeians, commoners, everyday life, Medieval, Middle Ages

Glossary

Skryptorium – pomieszczenie przeznaczone do ręcznego kopiowania kodeksów i przepisywania ksiąg. Znajdowały się w klasztorach, katedrach i kolegiatach.

Kopista – w średniowieczu osoba zajmująca się kopiowaniem i przepisywaniem dokumentów i ksiąg. Często nazywana była również skrybą.

Pokój Boży – wprowadzony przez Kościół katolicki w epoce średniowiecza zespół zasad zapobiegających wojnom prowadzonym przez panów feudalnych oraz stanowiący zabezpieczenie podróżnych przed napaściami.

Lichwa – nieetyczne pożyczki z zawyżonymi odsetkami. W średniowieczu za lichwę uważano pobieranie jakichkolwiek odsetek od zaciąganych pożyczek. Była potępiana przez Kościół jako sprzedaż czegoś, co nie istnieje.

Patrycjat – najzamożniejsza grupa mieszczan sprawująca rządy i posiadająca władzę ekonomiczną w mieście. Korzystała z przywilejów miejskich i uprawnień feudalnych.

Pospólstwo – w średniowieczu średniozamożna grupa zamieszkująca miasto (rzemieślnicy, drobni kupcy, sprzedawcy).

Plebs – najniższa warstwa społeczna w średniowiecznych miastach, najczęściej nie posiadająca majątku i miejskiego obywatelstwa, przez co odsunięta od udziału w życiu politycznym miasta.

Czeladnik – jeden ze stopni potwierdzających nabycie przez ucznia umiejętności dzięki, którym posiadał wiedzę rzemieślniczą.

Cech – związek zawodowo‑społeczny skupiający rzemieślników wykonujących ten sam zawód w danym mieście.

Gildia – stowarzyszenie zrzeszające kupców działających w danym mieście. Pełniła podobne funkcje co cech skupiający rzemieślników.

Stan – zbiorowość społeczna w eutopejskim społeczeństwie feudalnym