The Second Polish Republic Under the Sanation Government (revision class)

to define the effects of the May Coup D’État and the manifestations of the crisis of democracy;

to describe the everyday life of students of the elementary schools in the Second Polish Republic;

to characterize the strong and weak points of the economy and social life of the Second Polish Republic.

In 1926, Józef Piłsudski decided to take the power with the use of armed force. Ignacy Mościcki assumed the office of President. The August Novelization of 1926 became a temporary solution. One of the first decrees to be issued was the appointment of the General Armed Forces Inspector (Polish acronym: GISZ). Józef Piłsudski was appointed for this office by Ignacy Mościcki. In 1935, the April Constitution was adopted, limiting the authority of the Parliament. During the campaign for the new term of the Sejm in September 1930, the opposition leaders were arrested. Some of them were forced to emigrate. The Brest elections of November granted the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR) 56% of the seats in the Sejm and almost 68% in the Senate. It was a result of a violation of democratic principles. The founding of the Bereza Kartuska prison in the 30s became a symbol of the Sanation’s activities. On 12 May 1935, Józef Piłsudski died. After his death, President Mościcki took control of the government administration, Edward Rydz‑Śmigły was named the General Armed Forces Inspector, and in 1936, he was named Marshal.

The Second Polish Republic maintained friendly relations with Latvia and Romania only. The alliance with France was weakened due to the signing of the Locarno Treaties, which were unfavorable to Poland, in 1925. In 1932, the Polish‑Soviet pact of non‑aggression was signed in Moscow. In 1934, Poland and Germany signed the declaration of nonviolence in mutual relations.

According to the general census of 1921, Poland had 27 million inhabitants, with Poles constituting ca. 69% of the population. The remainder of the population consisted of Ukrainians (14%), Jews (8%), Belarusians (4%), Germans (4%), as well as Lithuanians, Czechs, and Tatars. Not long after the May Coup D’État, the economic situation improved. The port of Gdynia was expanded, and the construction of the Polish Coal Trunk‑Line connecting Gdynia with Silesia began. The Great Depression affected Poland at the beginning of the thirties of the twentieth century, striking mainly agriculture. The situation in industry became difficult as well. The economic situation of Poland gradually improved in connection with the improvement of the economic situation worldwide. In 1935, Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski became the Minister of Treasury, while simultaneously being a Deputy Prime Minister. He initiated the construction of the Central Industrial Region, which encompassed nearly 100 industrial plants.

Listen to the recording. How did the pupils of the Second Polish Republic’s elementary schools fare?

The female pupils of the first coeducational grade of the elementary school in Vilnius wrote essays titled “Who am I going to be when I grow up”. In 1931, they declared that they wished to become preschool headmistresses and treat the poor. The future ballerinas and actresses promised to dance in the hospitals, to “make the patients’ time more pleasant”. The boys would most commonly express interest in becoming aviators, sailors, boxers or soldiers of rank no lower than Colonel. “They were busy making war chaos in their notebooks” and “went missing in action en masse”. Even in the essay that they were asked to write by teacher Eugenia Kobylińska, titled “I am a postman”, “none of the postmen led a peaceful life. They were attacked by bandits, shot by thieves, and had to fight back using their fists, knives, and revolvers”. While conversing freely with the teacher, they would tell the teacher about their love for the “Detective” journal and the American movies about juvenile gangsters.

Good teachers were able to find understanding with the pupils that experienced poverty, war trauma, and the effects of the Great Depression. The teachers possessed the most up‑to‑date knowledge of the situation of the children, and would oftentimes deeply sympathize with them. Few of the children coming from families of workers and craftspeople had decent clothing and winter coats. None had gloves. Poverty, in every sense of the word, was apparent. “While playing, the children’s clothes would come apart, and the rips would show bare skin, with no underwear on it” – recalled Zofia Gruszczyńska, a teacher. Even in the schools of the Warsaw Voivodeship (let alone in the remote reaches of the Second Polish Republic!) the children were “poorly nourished and dressed, lice‑ridden”, and “they had to be given pencils and notebooks, as they had no money to buy them with”. They would come to school dressed in their “fathers’ shoes” and “mothers’ jerkins”. In 1937, a teacher wrote the following in a letter to the press: “In conditions where soap has become a legend, the talks of the hygiene of the body and the clothes are mere irony. The myth of domestic hygiene is an abstraction in the face of what the school itself looks like. The propaganda of frugality sounds like irony in places where the whole family shares one pair of shoes, one match is used to light four fires, and the same portion of salted water is used to boil four potfuls of potatoes”.

[Monika Piotrowska‑Marchewa, based on own research]

Analyze strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to social and economic life in the Second Polish Republic.

Weaknesses

Opportunities

Threats

Analyze the data pertaining to the height and weight of elementary and high school pupils in the Second Polish Republic.

What differences between the parameters pertaining to the elementary and high school pupils do you notice?

Among the truthful statements below, choose those that may serve as comments for the data contained in the table.

The height and weight of the elementary and high school students in the Second Polish Republic (1935)

Age | Elementary school | BMI | High school | BMI | ||

Height | Weight | Height | Weight | |||

10–‘11 | 131,2 | 27,8 | 16 | 136,3 | 32,0 | 18 |

11–12 | 135,0 | 30,2 | 17 | 139,2 | 34,0 | 18 |

12–13 | 139,2 | 31,5 | 16,5 | 143,7 | 36,1 | 18 |

13–14 | 144,1 | 35,7 | 18 | 151,8 | 42,1 | 19 |

14–15 | 148,3 | 38,8 | 18 | 154,1 | 43,5 | 19 |

15–16 | 151,3 | 41,3 | 18 | 161,8 | 50,3 | 20 |

BMI – the body mass index, calculated by dividing one’s body mass in kilograms by the squared height in meters.

Determine and mark whether the statements below are true or false.

| Statement | True | False |

| There was an educational gap between the countryside and the cities, inhabited by a mere 25% of the entire population of the Second Polish Republic. The majority of the countryside children only had access to single-class schools, where only the fourth-grade programme was taught. | □ | □ |

| The students of middle and high schools would usually not go to elementary school. On the other hand, the students of elementary schools would usually finish their education at the elementary level. | □ | □ |

| Graduating from elementary school permitted the pupils to neither become pupils of the higher grades of high school nor study at universities. Passing high-school programme exams was mandatory. Due to this, the more affluent parents sought to prepare their children for the exams for the lowest high school grade possible. | □ | □ |

| High school education was paid, therefore it was usually only the more affluent youth to study at this tier. | □ | □ |

| According to the hygienists’ examinations of children between 10 and 16 years of age, those attending elementary schools were shorter and markedly thinner than their high-school peers. | □ | □ |

| Compulsory education was often met with aversion by the traditionalist peasant classes. In the Second Polish Republic, the peasants’ children would, for the first time, attend school not only to acquire the skills of reading and writing, but also to obtain a broader knowledge of the world. | □ | □ |

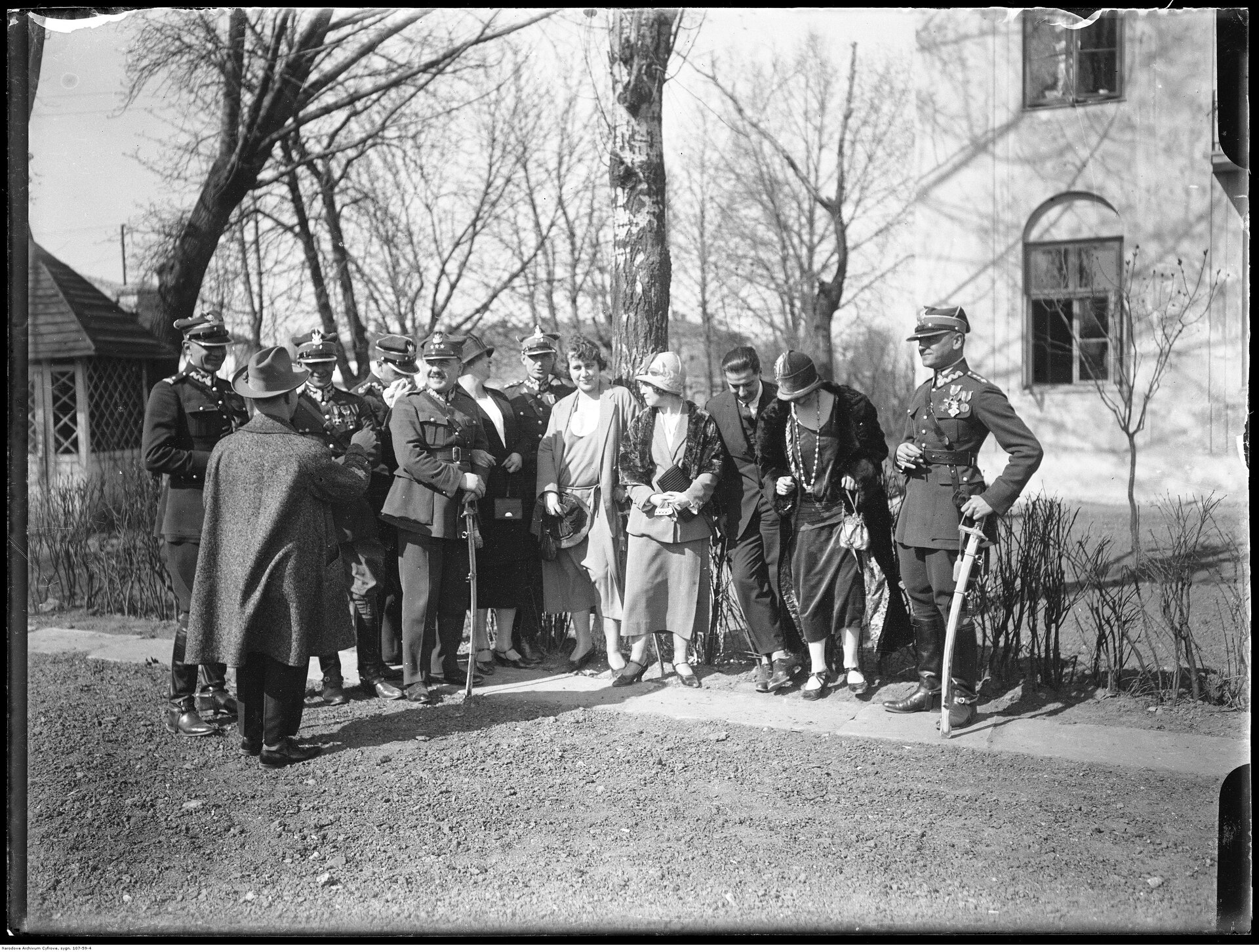

Easter in the 1st Mounted Artillery Division in Warsaw. The photographies below were made by Narcyz Witczak‑Witaczyński (1898‑1943), a Standard‑Bearer of the Cavalry of the Polish Army, a military photographer, knight of the War Order of Virtuti Militari. Compare the photographs. Show the differences between them. Try describing the emotions shown. Make up a story based on them.

Match the pairs: English words with Polish definition.

polityczne porozumienie działaczy stronnictw centrowych z 1936 r.; jego celem było zjednoczenie opozycji przeciw tendencjom autorytarnym i polityce zagranicznej obozu rządzącego po śmierci Piłsudskiego, naczelny organ sił zbrojnych w II RP; Generalny Inspektor przygotowywał i kontrolował wojsko w zakresie wszystkich spraw istotnych dla przyszłych zadań wojennych oraz personalnej obsady stanowisk w wojsku, ugrupowanie polityczne zwolenników rządów J. Piłsudskiego, partia łącząca grupy o różnych rodowodach i programach politycznych, obóz koncentracyjny; kierowano do niego osoby oskarżone o "naruszenie bezpieczeństwa lub porządku publicznego", w szczególności działaczy ONR, komunistów i ukraińskich nacjonalistów, radykalna prawicowa organizacja polityczna, powołana w 1926 z inicjatywy R. Dmowskiego, sojusz opozycyjnych partii lewicowych i centrowych, zawiązany w 1929 roku., nielegalna organizacja polityczna powstała w 1935; działała głównie na wyższych uczelniach, głosiła hasła nacjonalistyczne, antysemickie i prokatolickie, sposób sprawowania władzy opierający się na autorytecie przywódcy lub grupy osób podejmujących decyzje w najważniejszych sprawach państwowych, zespół fortyfikacji, dawna twierdza rosyjska nad Bugiem, przy ujściu Muchawca koło Brześcia

| Authoritarianism | |

| Bereza Kartuska prison | |

| Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR) | |

| Centrolew | |

| Front Morges | |

| General Armed Forces Inspectorate | |

| Camp of National Unity | |

| ONR Falanga | |

| Brest Fortress |

Keywords

Authoritarianism, Bereza Kartuska prison

Glossary

Autorytaryzm – sposób sprawowania władzy opierający się na autorytecie przywódcy lub grupy osób podejmujących decyzje w najważniejszych sprawach państwowych, najczęściej z pominięciem organów konstytucyjnych państwa

Bereza Kartuska – obóz koncentracyjny, utworzony rozporządzeniem prezydenta Ignacego Mościckiego w 1934 r., jako reakcja na zabójstwo ministra Bronisława Pierackiego dokonane przez ukraińskiego nacjonalistę; istniał do 1939 r., kierowano do niego osoby oskarżone o „naruszenie bezpieczeństwa lub porządku publicznego”, w szczególności działaczy ONR, komunistów i ukraińskich nacjonalistów

Nagranie dostępne na portalu epodreczniki.pl

Nagranie słówka: Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR)

Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem (BBWR) – ugrupowanie polityczne zwolenników rządów J. Piłsudskiego, powołane w 1928; partia łącząca grupy o różnych rodowodach i programach politycznych; wspólne im było podporządkowanie się autorytetowi Piłsudskiego, uznanie dominującej roli państwa w tworzeniu reguł życia społecznego, poparcie dla zasady silnej władzy państwowej, odrzucenie nacjonalizmu, dążenie do odgrywania przez Polskę samodzielnej roli na arenie międzynarodowej; po śmierci J. Piłsudskiego rozwiązany na skutek wewnętrzny tarć

Centrolew – sojusz opozycyjnych partii lewicowych i centrowych, zawiązany w 1929 roku.

Front Morges – polityczne porozumienie działaczy stronnictw centrowych z 1936 r., zainicjowane przez generała W. Sikorskiego i J. Paderewskiego, z udziałem W. Witosa i J. Hallera. Zawarte 17 II 1936 w Szwajcarii, w siedzibie Paderewskiego Riond‑Bosson w Morges (stąd nazwa), jego celem było zjednoczenie opozycji przeciw tendencjom autorytarnym i polityce zagranicznej obozu rządzącego po śmierci Piłsudskiego

Generalny Inspektorat Sił Zbrojnych – naczelny organ sił zbrojnych w II RP; utworzony dekretem Prezydenta RP z sierpnia 1926; Generalny Inspektor przygotowywał i kontrolował wojsko w zakresie wszystkich spraw istotnych dla przyszłych zadań wojennych oraz personalnej obsady stanowisk w wojsku; w 1939 stał się wodzem naczelnym

Obóz Wielkiej Polski – radykalna prawicowa organizacja polityczna, powołana w 1926 z inicjatywy R. Dmowskiego

Obóz Zjednoczenia Narodowego – próba kontynuacji BBWR; partia prorządowa utworzona w 1937 w celu skupienia społeczeństwa wokół armii i marszałka E. Rydza‑Śmigłego

ONR‑Falanga – nielegalna organizacja polityczna powstała w 1935 w wyniku rozłamu dokonanego przez B. Piaseckiego w Obozie Narodowo‑Radykalnym, który z kolei wyodrębnił się podczas kryzysu politycznego w Narodowej Demokracji; działała głównie na wyższych uczelniach, głosiła hasła nacjonalistyczne, antysemickie i prokatolickie, miała wsparcie Kościoła katolickiego, a od 1936 przez pewien czas współpracowała z sanacyjnym Obozem Zjednoczenia Narodowego; liczyła ok. 5 tys. członków.

Twierdza w Brześciu nad Bugiem – zespół fortyfikacji, dawna twierdza rosyjska nad Bugiem, przy ujściu Muchawca koło Brześcia