Threats and promises: The partitioners’ policy for Polish lands

to list the rulers of Polish lands in the second half of the 19th century;

to characterize the different situations of Poles under three partitions;

to define the methods used by the partitioners.

Until the beginning of the 1860s, the issue of Poland was a fixed item in the political agenda of European countries. The situation changed with the defeat of the January Uprising, and the fall of the Second French Empire and the Paris Commune, as of which the official European political stage became silent. Following the defeat of the January Uprising, the imperial authorities abolished the autonomyautonomy of the Kingdom of Poland and created the Vistula Land in its place. This was a period of intense RussificationRussification, especially in the fields of administration and education. A similar policy was adopted by the Prussians, who commenced intensified GermanisationGermanisation in Greater Poland. The fight against the Church earned the name KulturkampfKulturkampf and was fought simultaneously in Prussia and throughout Germany. GermanisationGermanisation affected settlements as well. 1885 marked the beginning of compulsory displacements, which Polish people referred to as Prussian deportations. The situation was different in Galicia, which, thanks to internal reforms in the Habsburg Empire, was granted broad administrative and educational autonomyautonomy. There, Polish people could freely organise national ceremonies, anniversaries and jubilees.

Put the partitioning rulers who in the second half of the 19th century decided Polish matters into the appropriate column.

<strong>King Frederick William IV Hohenzollern </strong>1795–1861, <strong>Emperor William I Hohenzollern</strong>1797–1888, <strong> Emperor Alexander III</strong>1845–1894, <strong>Emperor Franz Joseph I Habsburg</strong>1830–1916, <strong>Emperor Alexander II Romanov </strong>1818–1881, <strong> Emperor Wilhelm II Hohenzollern</strong>1859–1941, <strong>Emperor Nicolas II</strong>1868–1918

| Austria/Austria-Hungary | |

|---|---|

| Russia | |

| Prussia/Germany |

Read the information below and describe RussificationRussification.

Following the defeat of the January Uprising, Russia completely changed its policy for the Polish people. The first sign of this change was the emancipation reform, which started during the uprising and was purposefully conducted in a manner that was unfavourable for the nobility. In 1861, martial law was introduced in the Kingdom of Poland and lasted for 40 years. The presence of the Russian army, confiscation of property and exile became a permanent image in the difficult landscape of Polish people’s reality until the end of the 19th century. People were arrested without trial on the basis of administrative decisions (people, especially the nobility, from the Taken Lands were exiled on a large scale). Any and all political activity was forbidden and associations were prohibited in order to hinder the social activity of Poles. The element that Russification targeted the most was education. The Main School established at the time of Aleksander Wielopolski was replaced with a Russian university. Alexandr Apukhtin, the superintendent of the Warsaw education district, made Russian a compulsory language in all types of schools (only religion was taught in Polish) in 1880.

Read the information below and describe GermanisationGermanisation.

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck wanted to strengthen the newly united Germany. In his opinion, this process was being hindered by the Catholic Church and ethnic minorities, including the Polish minority (mostly in Poznańskie, but also in Upper Silesia where Karol Miarka was undertaking nation‑related activities). In 1872, Bismarck attempted to make the Catholic Church subordinate to German state structures (the so‑called Kulturkampf). His campaign covered the entire area of Germany. Clergymen were deprived of their influence over education, monastery schools were closed, and civil marriages and divorces were introduced. Nevertheless, Bismarck strengthened the relationship between the Catholic faith and Polishness instead of weakening it, and ultimately lost his battle. 1876 marks the beginning of the de‑Polonisation of courts, the education system (especially at the secondary level) and offices. Only religion and church singing classes could be taught in Polish and even then those were only in the lowest grades. Polish people could not be granted permits to run private schools and no permit was granted to establish a university.

As of 1885, Polish and Jewish economic emigrants without German citizenship were compulsorily displaced (in so‑called Prussian deportations). They later became a symbol of Bismarck’s anti‑Polish policy. A year later, the Colonisation Committee was established to support Germans settling in the east of the Reich, but Germans from the east preferred to go to the west of Germany. Unlike in the lands annexed by Russia, there was no bribery on lands annexed by Prussia. Exercising their constitutional rights, Poles could take the authorities to trial and take part in political life. Nevertheless, there was no space for Polishness.

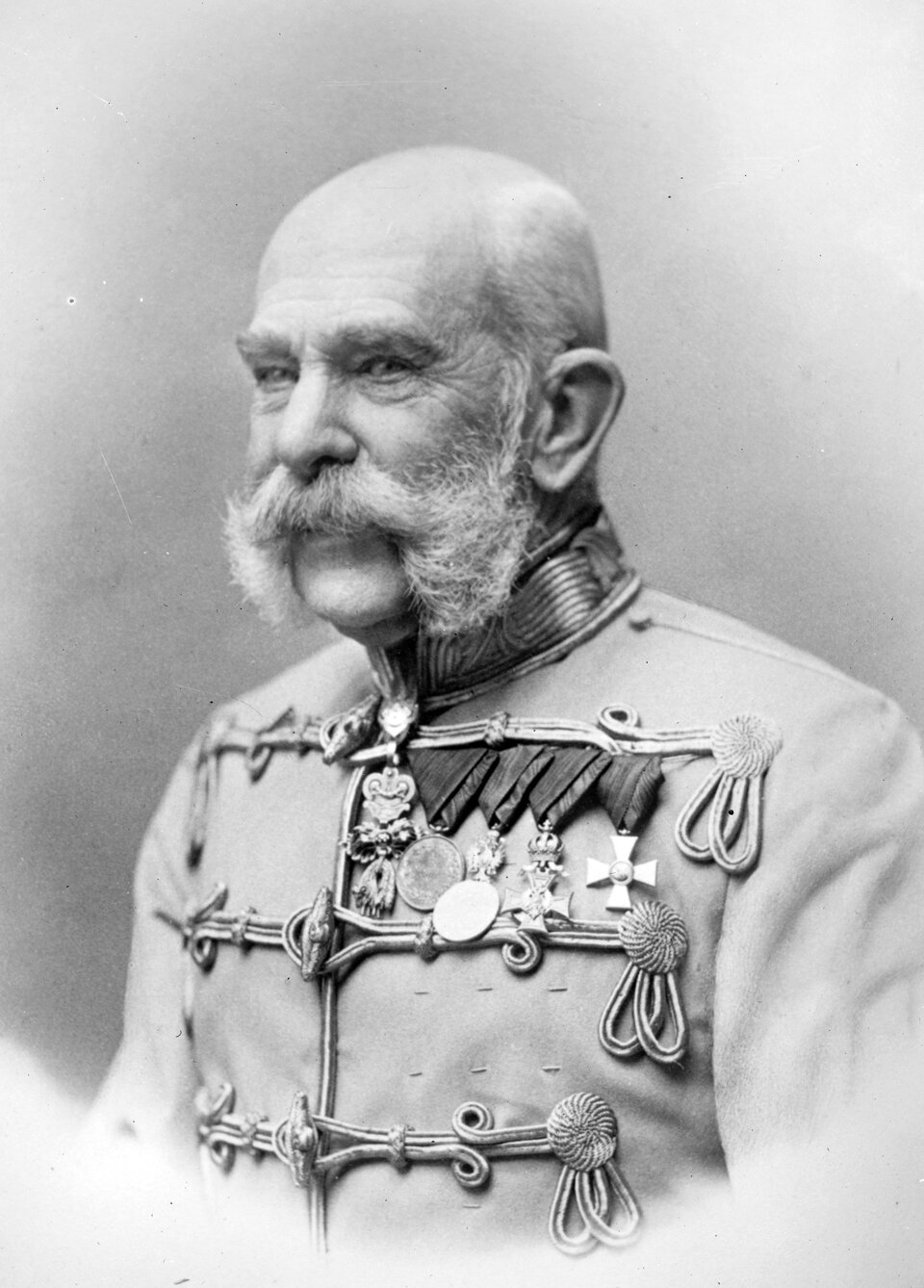

Listen to the recording. What kind of a ruler was Franz Joseph? What was the attitude of the Polish subjects to the emperor?

„Franz Joseph lived for 86 years, and ruled continuously for 68 years. During his reign, in the period between the Spring of Nations and the end of the First World War, his country was transformed from absolute to constitutional monarchy. Almost three generations passed, fashions and preferences changed (not as fast as today, of course), and the emperor remained and ruled to become a symbol of continuity, stabilisation and liberalism. […]

The strongest supporters of the Habsburg throne in Galicia were the officials and peasants. The reasons why the officials admired Franz Joseph were clear: for them, he was not only their ultimate superior, but also a model example of professional diligence and conscientiousness. His Majesty would personally settle all personnel matters in his empire. He signed nominations for all officials, regardless of whether they were of high or medium rank. He decided on any and all awards and promotions. The anecdote about Franz Joseph stating “independent official” in the profession column during the census might actually be true. It shows how Franz Joseph’s mentality was that of a solid German official who settled all matters fairly and impartially, with care for the slightest detail […].

On the other hand, Galician peasants saw the emperor as a just and kind‑hearted ruler. This opinion actually regarded the institution of the head of state, which means it concerned subsequent emperors: Francis I, Ferdinand I and, last but not least, Franz Joseph. The persistence of these feelings towards an idealised ruler is understandable in the light of the harsh reality of poverty, the indifference of officials and the unwillingness of landowners to make any compromises in favour of the peasantry. 1846 deepened mutual prejudice, as the nobility, scared by the Galician Slaughter, moved away from the peasants, as did the intelligentsia and the Democrats.

[…] Jan Słomka [peasant and memoirist], who remembered the time of serfdom, mentioned how deeply the belief in imperial justice was rooted in the peasantry. As Słomka wrote, if anyone felt wronged by a nobleman or an official, they would say that they “would go to the emperor and find justice there”. Peasants were sure that nobody was as just as the emperor himself. The memory of the emperor abolishing serfdom in Galicia was so well preserved that even at the end of the 19th century peasants associated the possibility of rebuilding independent Poland with... the return of serfdom. Although peasants’ opinion of the nobility was very negative, “everybody referred to Emperor Franz Joseph with unbelievable respect, and considered him to be an embodiment of wisdom, infallibility and, most of all, absolute justice. They all deeply believed that if he had not defended and supported peasants, their fate would have been much worse”.

Regardless of the fact that after 1846 Galician peasants considered the Austrian emperor their protector and defender, the nobility continued to consider Austria as the most dangerous partitioner for many years to come. Twenty years later, an agreement would be concluded with Emperor Franz Joseph, and the Habsburg monarchy would be regarded as the best of the partitioners. Following the collapse of Austria‑Hungary, Galician nobility would long remember the rule of Franz Joseph I, which they considered to be a golden age.

Source: Z. Fras, Galicja, Wrocław 1999, pp. 249–251

Which authorities committed the below partition-related actions in the second half of the 19th century (as of 1848)?

| Partitioning authorities | Russia | Germany | Austria |

| Settlement campaign | □ | □ | □ |

| Kulturkampf | □ | □ | □ |

| Polonization of education | □ | □ | □ |

| Fight against the Uniate Church | □ | □ | □ |

| Introduction of autonomy | □ | □ | □ |

| Exile and confiscation of property | □ | □ | □ |

Keywords

Kulturkampf, autonomy, Germanisation, Russification

Glossary

Kulturkampf – polityka Bismarcka w latach 1871‑1878, zmierzająca do ograniczenia wpływów Kościoła Katolickiego w II Rzeszy i w Prusach.

Autonomia – prawo gwarantowane przez państwo do samodzielnego rozstrzygania spraw wewnętrznych przez wspólnotę, mniejszość narodową lub jednostkę prawną (np. uniwersytet)

germanizacja – polityka Prus prowadząca do rozpowszechnienia języka niemieckiego i niemieckiej świadomości narodowej wśród mieszkańców ziem, zajętych w wyniku rozbiorów

rusyfikacja – polityka Rosji prowadząca do rozpowszechnienia języka rosyjskiego i rosyjskiej świadomości narodowej wśród mieszkańców ziem, zajętych w wyniku rozbiorów