Przeczytaj

The picture below shows a happy face with dollar signs for eyes, obviously suggesting that money can make you happy. It’s so easy to say that money doesn’t buy happiness, but does that mean that life without it is easy? Is it really so that we only need friends, family and job satisfaction? Read the texts below that present some arguments in the never‑ending money or job satisfaction debate.

Poniższa ilustracja przedstawia zadowoloną twarz z dolarami w oczach, co w oczywisty sposób sugeruje, że pieniądze mogą uczynić człowieka szczęśliwym. Łatwo powiedzieć, że nie da się kupić szczęścia, ale czy to oznacza, że życie bez pieniędzy jest proste? Czy rzeczywiście jest tak, że potrzebujemy tylko przyjaciół, rodziny i satysfakcji z pracy? Przeczytaj poniższe teksty, w których przedstawiono niektóre argumenty przytaczane w niekończącej się debacie: pieniądze czy satysfakcja z pracy.

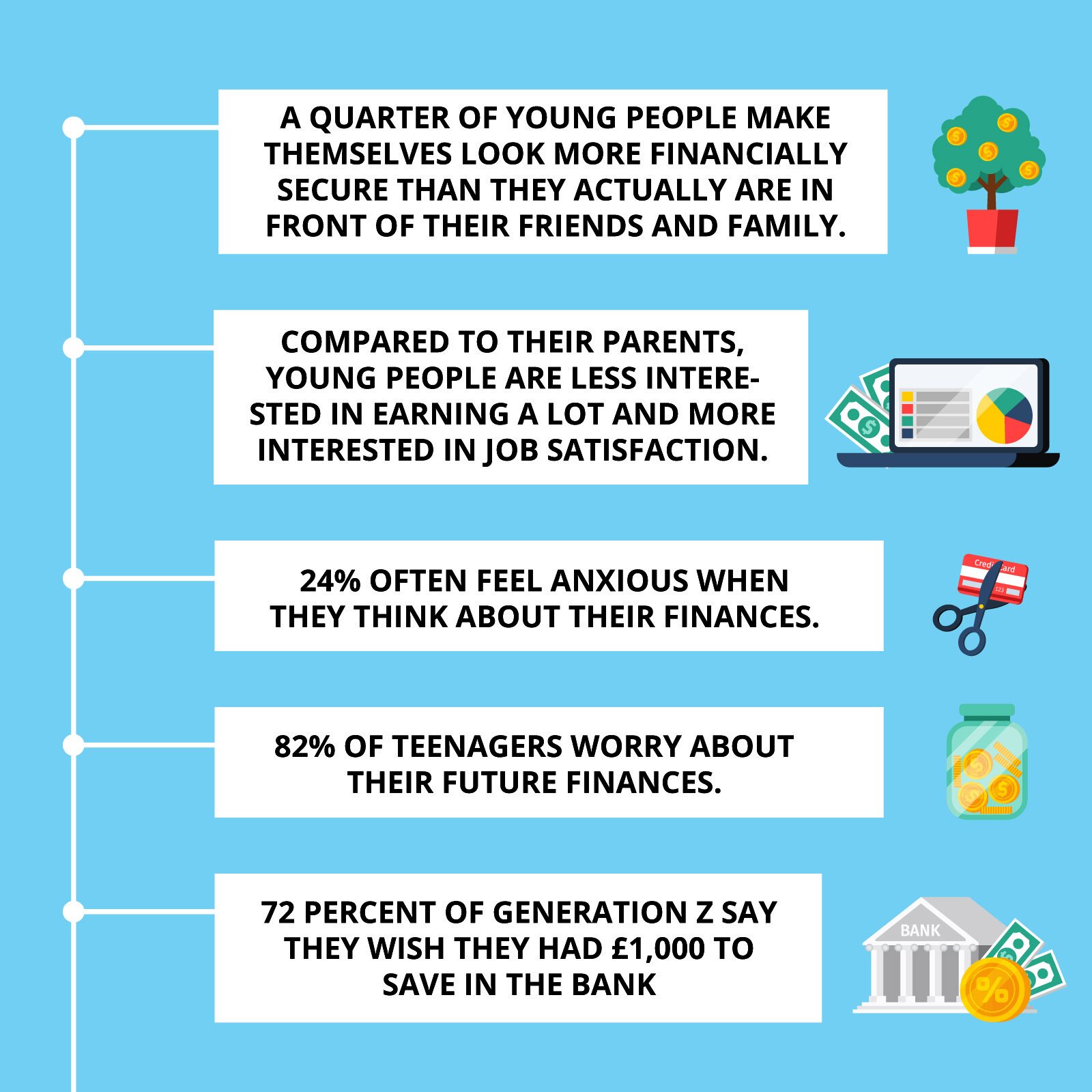

Look at the infographic below and choose the correct answer True (T) or False (F).

Let’s Look at LukeText A

With the age difference between us, I’d never had much to talk about with my brother Luke and, until three years ago, I’d never looked up to him. In my eyes, he’d always been a nerd, with his nose in the books. Then, Luke got a well‑paidwell‑paid job with a big company. He has since moved out and, although throwing money aroundthrowing money around, he’s never in the redin the red. Now, that’s life! I wish our parents had a budgetbudget like that. If they had what he has: a good incomeincome with great fringe benefitsfringe benefits, like a company car and a laptop… well, let’s just say our lives would be easier. Look at my brother. The perksperks saved him a pretty pennypretty penny so he bought a huge TV and now, whenever there’s a football game, he invites me to watch it at his place. I’m not saying it’s easy moneyeasy money, mind you. He does work a lot, often working overtimeovertime and weekends. Last week, my mom’s birthday? He only stuck his nose out for five minutes when she was blowing out the candles and spent the rest of the night occupying his old room because he had a „crisis at work.” That takes some serious determinationdetermination. Mom was a bit upset and said she’d rather he sat with us, but he said there was nothing he could do about it. But then, look on the bright side — he has money to burnhas money to burn now and he got her the coffee maker she’d been dreaming of. He doesn’t have to worry about bills and doesn’t have to deny himself much. I’d rather work a bit less than he does but maybe it’s worth it, you know? Our parents always had problems making ends meetmaking ends meet, and I’d rather not live my entire life wishing I had things I would never be able to afford.

Text B

Money or job‑satisfaction? Material pleasures or general contentmentcontentment? It’s always a difficult question. Spending one third of your life (8 out of 24 hours a day) in some place and wishing you were somewhere else can be a cause of frustration. On the other hand, studies show that people who are well‑offwell‑off and don’t need to worry about the bare necessitiesbare necessities definitely feel happier. From that perspective, money does buy happiness. Having a roof over your head and being able to afford clothes, equipment, healthcare, and holidays gives the well‑to‑do a sense of securitysense of security and, let’s be honest, a lot of pleasant moments. Passions can make your life worth living, but what if yours happens to be expensive, like horse riding or travelling to exotic destinations? Playing chess or camping in the nearby woods is fun, but not if you’d rather be doing something else. Working for peanutsWorking for peanuts means having to choose what you buy this month and what has to wait for next month or a pay risepay rise. It’s having to live where you can affordafford, not where you want. It’s putting some plans and dreams on the ‘one day when I get a bonusbonus’ shelf. A good salarysalary is a ticket to freedom. Freedom of choice. It doesn’t mean job satisfactionjob satisfaction isn’t important. By no means should you take a job you hate or work yourself into the groundwork yourself into the ground to earn as much as possible. But it’s up to you to decide what you need to do at each stage of your life.

Źródło: Joanna Sobierska‑Paczesny, dostępny w internecie: https://www.marketingweek.com/inside-the-financially-savvy-minds-of-gen-z/ [dostęp 23.06.2023], https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/generation-z-money-survey/ [dostęp 23.06.2023], licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0.

- In text A, what’s the relationship between the author and his brother?

a) The author doesn’t look up to his brother.

b) The author’s brother recently earned his admiration.

b) The author doesn’t understand his brother’s life choices.

c) They never really talk or spend time with each other.

- The author of text A recalls their mom’s birthday in order to

a) show what his brother’s life is like now that he has a job.

b) give an example of the things that his brother can afford now.

b) make the reader understand why he won’t choose a similar path.

c) criticise his brother’s behaviour towards their parents.

- What does the author of text A mean by saying "maybe it’s worth it"?

a) Sacrificing some things in your life so that you don’t have to worry about money.

b) Having a family even if it means problems with making ends meet.

b) Upsetting someone but being able to buy them things they dream of.

c) Working and earning less but having more time for the family.

- Which is true about texts A and B?

a) They present opposing points of view.

b) The author of A would only partially agree with the author of B.

b) The author of text B probably got his ideas from text A.

c) Both texts have the same main idea about money.

- The best title for text B would be:

a) How to earn a good salary.

b) Money matters.

b) Job satisfaction is the key.

c) Money doesn’t buy happiness.

- If you 1. make ends meet, 2. work for peanuts, 3. throw money around, 4. have money to burn, 5. work yourself into the ground, 6. fringe benefits, 7. easy money, you work way too much.

- To 1. make ends meet, 2. work for peanuts, 3. throw money around, 4. have money to burn, 5. work yourself into the ground, 6. fringe benefits, 7. easy money is to spend a lot on things that aren’t necessary.

- People who 1. make ends meet, 2. work for peanuts, 3. throw money around, 4. have money to burn, 5. work yourself into the ground, 6. fringe benefits, 7. easy money have so much they don’t know what to do with it.

- If you 1. make ends meet, 2. work for peanuts, 3. throw money around, 4. have money to burn, 5. work yourself into the ground, 6. fringe benefits, 7. easy money you’re getting paid very little.

- To say it was 1. make ends meet, 2. work for peanuts, 3. throw money around, 4. have money to burn, 5. work yourself into the ground, 6. fringe benefits, 7. easy money means someone earned it illegally or without too much effort.

- If you 1. make ends meet, 2. work for peanuts, 3. throw money around, 4. have money to burn, 5. work yourself into the ground, 6. fringe benefits, 7. easy money you have enough money to get from one month to the next.

- If you get 1. make ends meet, 2. work for peanuts, 3. throw money around, 4. have money to burn, 5. work yourself into the ground, 6. fringe benefits, 7. easy money that means that apart from money you’re getting things like a company car or computer.

- In text A, Luke spends a lot of money Tu uzupełnij financial problems. (HAVE)

- In text A, the author’s parents Tu uzupełnij a lot of money. (EARN)

- Text B suggests that you might Tu uzupełnij (GET) if you spend 33% of your life in a place Tu uzupełnij. (LIKE)

- In text B, playing chess is given as an example of a Tu uzupełnij. (CHEAP)

- In text B the phrase ‘ticket to freedom’ means that a good salary Tu uzupełnij you want. (ALLOWS)

GRAMATYKA

Wyrażenie ,,osoba + wish'' stosujemy, aby wyrazić życzenie lub żal. Przetłumaczymy go jako “chciałbym/chciałabym''” lub “żałuję, że .../szkoda, że...”. Używamy go, aby mówić o hipotetycznej teraźniejszości, przyszłości, przeszłości lub aby wyrazić zniecierpliwienie/poirytowanie obecną sytuacją, na którą nie mamy wpływu.

W zależności od kontekstu, stosujemy następujące czasy gramatyczne:

I wish + Past Simple / Past Continuous (zdania dotyczą teraźniejszości).

Przykłady:

I wish I had money. - Żałuję, że nie mam pieniędzy.

I wish you were here. - Szkoda, że cię tu nie ma.

She wishes she wasn't working late today. - Ona żałuje, że dziś pracuje późno.

I wish + Past Perfect / Past Perfect Continuous (zdania dotyczą przeszłości).

Przykłady:

I wish I hadn't fought with my boss. - Szkoda, że posprzeczałem się z moim szefem.

He wishes he had remembered about your birthday. - On żałuje, że nie pamiętał o twoich urodzinach.

We wish we had gone with you that day. - Żałujemy, że nie poszliśmy z wami tamtego dnia.

I wish + would/could + czasownik (zdania dotyczą przyszłości).

Przykłady:

I wish it would stop raining. - Chciałbym, żeby przestało padać.

She wishes they wouldn't make so much noise in front of her house. - Ona chciałaby, żeby nie robili tyle hałasu przed jej domem.

They wish they wouldn’t work such long hours every day. - Oni chcieliby nie pracować tak długo każdego dnia.

WOULD RATHER

Konstrukcji z would rather używamy, aby wyrazić niezadowolenie lub preferencje dotyczące istniejącej sytuacji lub brak jej spełnienia w przeszłości. W zależności od sytuacji zdania konstruujemy w jeden z następujących sposobów:

Gdy mówimy o sobie:

Sytuacja obecna: He doesn’t work from home.

Nasze preferencje: He’d rather work from home.

Sytuacja trwająca obecnie: She’s working late today.

Nasze niezadowolenie: She'd rather not be working late today.

Sytuacja w przeszłości: I heard from a coworker about my transfer.

Nasze niezadowolenie: I’d rather not have heard from a coworker about my transfer.

Gdy mówimy o kimś/czymś innym:

Sytuacja obecna: My office doesn’t have any windows.

Nasze preferencje: I’d rather my office had some windows.

Sytuacja trwająca obecnie: My mom is working late today.

Nasze niezadowolenie: I’d rather my mom wasn’t working late today.

Sytuacja w przeszłości: He divided the work without consulting with me.

Nasze niezadowolenie: I’d rather he hadn’t divided the work without consulting with me.

HAD BETTER

Konstrukcji had better (lepiej by było, żeby...) używamy, by zasugerować jakieś działanie. Myśl o niej jako o konstrukcji bliskoznacznej do should.

Przykład:

You should start working on it as soon as possible. = You’d better start working on it as soon as possible.

I should go now. = I’d better go now.

GET ARRIVE LEAVE FIND You’d better Tu uzupełnij this to someone more experienced. She’d better Tu uzupełnij soon or the meeting will start without her. I’d better Tu uzupełnij a solution to this problem fast. We’d better Tu uzupełnij some rest.

2. I wish my parents have had a job like that.

3. She wishes she had chosen will choose a different career.

4. She’d rather he sits sat with us.

5. I’d rather work working a bit less.

6. I’d ratherdon’t live not live my entire life in debt.

7. Would you rather be doing had done something else?

8. You’d better saving save some money for a rainy day.

SŁOWNIK

/ əˈfɔːd /

pozwolić (sobie na coś)

(to be able to buy or do something because you have enough money or time)

/ beə nɪˈsesɪtɪz /

podstawowe minimum, najpotrzebniejsze rzeczy

(only the most basic or important)

/ ˈbəʊnəs /

premia

(an extra amount of money that is given to you as a present or reward for good work as well as the money you were expecting)

/ ˈbʌdʒət /

budżet

(the amount of money you have available to spend)

/ kənˈtentmənt /

zadowolenie

(happiness and satisfaction, often because you have everything you need)

/ dɪˌtɜːmɪˈneɪʃn̩ /

determinacja

(the ability to continue trying to do something, although it is very difficult)

/ ˈiːzi ˈmʌni /

łatwo zarobione pieniądze

(money that is easily and sometimes dishonestly earned)

/ frɪndʒ ˈbenɪfɪts / / frɪndʒ ˈbenɪfɪt /

świadczenia dodatkowe [świadczenie dodatkowe]

(something that you get for working, in addition to your pay, that is not in the form of money)

/ ˈhæz ˈmʌni tə bɜːn / / həv ˈmʌni tə bɜːn /

(idiom) mieć za dużo pieniędzy (have too much money)

/ ɪn ðə red /

pod kreską, z długami

(spending more money than you earn)

/ ˈɪnkʌm /

dochód

(money that is earned from doing work or received from investments)

/ dʒɒb ˌsætɪsˈfækʃn̩ /

satysfakcja z pracy

(the feeling of pleasure and achievement that you experience in your job when you know that your work is worth doing, or the degree to which your work gives you this feeling)

/ ˈmeɪk dɪˈmɑːndz ɒn / / ˈmeɪkɪŋ endz miːt /

wiązał/wiązała koniec z końcem [związać koniec z końcem]

(to have just enough money to pay for the things that you need)

/ ˈəʊvətaɪm /

nadgodziny

(time spent working after the usual time needed or expected in a job)

/ ˈpeɪ raɪz /

podwyżka

(an increase in the amount of money you earn for doing your job)

/ pɜːks / / pɜːk /

dodatkowe korzyści [dodatkowa korzyść]

(an advantage or something extra, such as money or goods, that you are given because of your job)

/ ˈprɪti ˈpeni /

niezła kasa, duża suma pieniędzy

(a large amount of money)

/ ˈsæləri /

pensja (zwykle wypłacana co miesiąc)

(a fixed amount of money agreed every year as pay for an employee, usually paid directly into his or her bank account every month)

/ ˈthetarəʊɪŋ ˈmʌni əˈraʊnd / / ˈthetarəʊ ˈmʌni əˈraʊnd /

szasta pieniędzmi [szastać pieniędzmi]

(to spend money, especially in an obvious and careless way, on things that are not necessary)

/ wel ɒf /

dobrze sytuowany/sytuowana, zamożny/zamożna

(rich)

/ wel peɪd /

dobrze płatny/płatna

(earning a lot of money)

/ ˈwɜ:k jɔːˈself ˈɪntə ðə ɡraʊnd /

przepracowywać się

(to make yourself very tired by working too much)

/ ˌwɜ:kɪŋ fə ˈpiːnʌts / / ˈwɜ:k fə ˈpiːnʌts /

praca za marne grosze [pracować za marne grosze]

(to work for a very small payment)

Źródło: GroMar Sp. z o.o., licencja: CC BY‑SA 3.0