Nobles’ Democracy

to characterize who the nobilitynobility were;

to describe how did the Polish Nobles’ DemocracyNobles’ Democracy develop;

to explain why did the kings confer privileges;

to define what were the sejmiks and the General SejmGeneral Sejm, and what were their tasks;

to indicate where did the liberum vetoliberum veto principle come from.

The fourteenth century saw the birth of a new social class – the nobility. It came into being as a derivation of the knight class. The umbrella term “nobility” captures the magnates, the middle‑tier and croft nobles, and landless nobles (gołota). Since the second half of the fourteenth century, especially during the rule of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the nobility gained ever more privileges. This state first obtained an advantage over the burgesses, and later over the clergy. In the end, the rulers were forced to allow the nobility’s participation in the legislative process – adopting laws and especially imposing taxes. Since the fifteenth century, the gatherings of nobility in every Voivodeship earned the name of “sejmiks”.

The gatherings of the monarch, the SenateSenate and the representatives of the sejmiks were called the general Sejm. The first general Sejm took place in 1493 in Piotrków. The Sejm adopted the law, i.e. mainly imposed taxes, announced the more important changes to the law, and controlled the state’s decisions pertaining to its foreign policy. It was the Sejm’s task to declare war and make peace. Any gatherings of the nobility without the participation of the monarch could be viewed as a mutiny against him. This kind of gathering was known as rokoszrokosz. The gatherings of the nobility called to support the actions of the monarch were called “confederationsconfederations”.

The Polish Sejm operated under the principle of unanimity. In order for a new law to be adopted, every member of the gathering had to give his consent. This meant that one envoy could prevent a law from being passed. This principle was known as the “liberum veto”, i.e. the principle of free voice.

The members of the Polish nobility distinguished themselves with their appearance. Show the particular elements of their appearance and attire:

kontusz (split‑sleeve overcoat)

żupan,

sabersaber,

moustache

broad belt

dyed skin shoes.

Analyze the timeline and reflect upon the reasons why the monarchs conferred ever more privileges upon the nobility. Why would the rulers make concessions to their subjects?

Between the second half of the fourteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth century, the nobility received general privileges that guaranteed its members participation in the state’s power, as well as the dominant and undisputable position in society.

Analyze the table, then complete the exercises.

The social structure of the Polish‑Lithuanian Commonwealth | |||

Social Class | Nobility | Burgesses | Peasants |

Profession | landowners | trade and craft | agriculture |

Defense of the country | yes | no | no |

Political rights | yes | no | no |

Which social class had the given duties and privileges?

| Privilege | Nobility | Burgesses | Peasants |

| Political rights | □ | □ | □ |

| Trade and craft | □ | □ | □ |

| Owning land | □ | □ | □ |

| Defense of the country and war expeditions | □ | □ | □ |

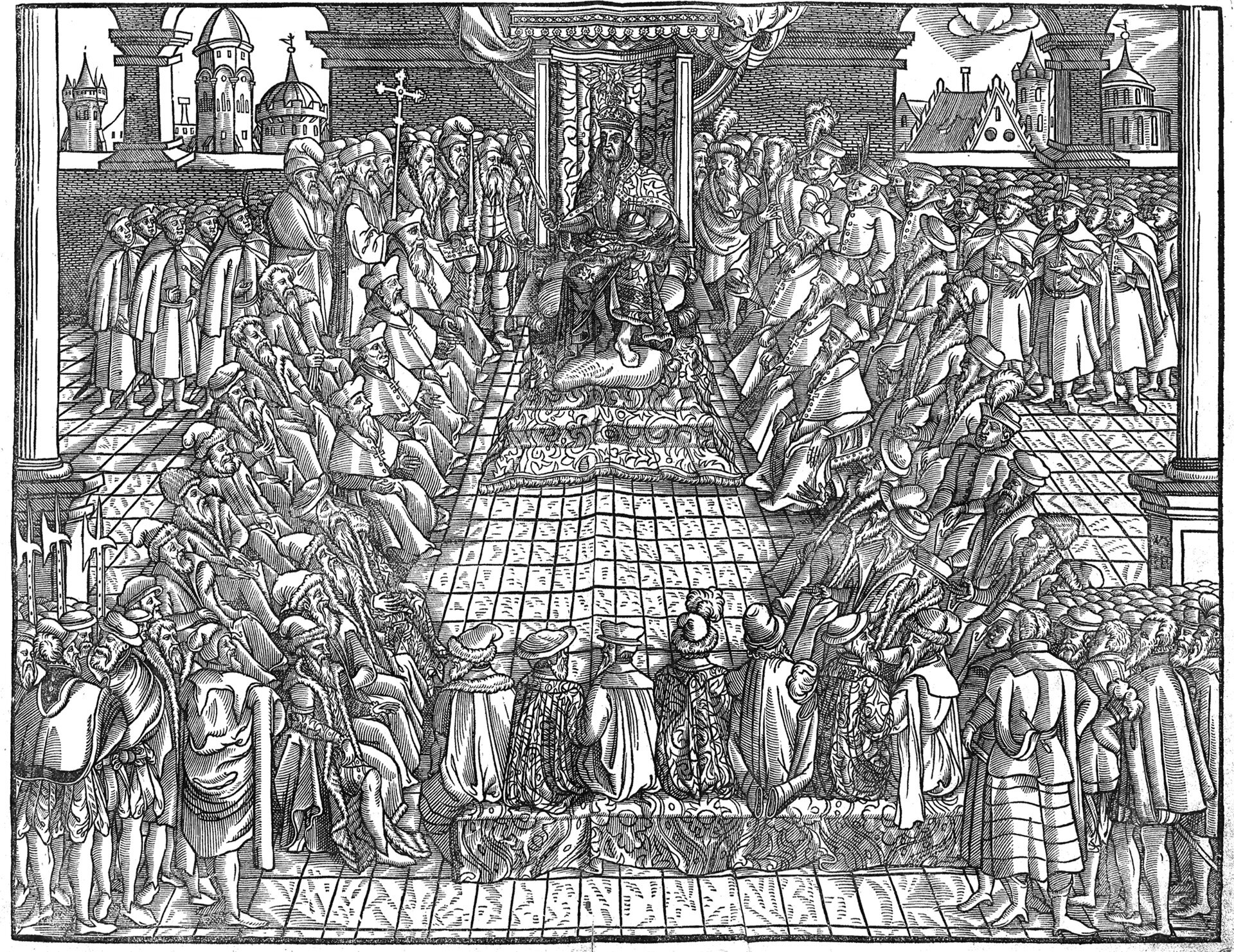

Look carefully at how the sejmiks, the sessions of the Senate and the general Sejm were portrayed, then complete the exercise.

Indicate the true sentences.

- The sejmiks were quiet and orderly.

- For the nobility a sejmik was also an opportunity to party and socialize.

- The sejmiks took place in churches.

- The sejmiks were poorly frequented by the nobility.

- The nobility came to the sejmiks with their weapons.

Read the text carefully, then complete the exercise.

Starting at dawn, there was a great commotion in the little, sleepy town of Środa Wielkopolska. Many people were walking about in the streets, chariots, carriages and groups of riders passed the narrow lanes. The local inns, normally empty, were unusually bustling with life. The chimneys emitted smoke, the cooks were preparing enormous amounts of food. In front of one of the inns, a few young lads were carefully unloading barrels of mead, wine and beer off a heavy cart. Their work was overseen by an elderly man, who shouted at the servants to be careful when handling them. He was the confidant of an important official – Krzysztof Opaliński, the Voivod of Poznań, who was to arrive in the town soon in order to take part in the local sejmik. A sizable number of noblemen from Greater Poland had already come. It is in the little Środa where the sejmik of two Voivodeships – poznańskie and kaliskie – was to take place. A well‑built nobleman wearing a green kontusz, a tall cap and a pair of tall, vivid‑yellow boots, approached the two youngsters unloading the carts. He slid his left thumb behind his broad belt, at which hung a curved saber, its hilt adorned with precious stones. With his right hand, he twirled his long moustache.

– I see the carts of the Voivod have arrived already? – he said to the servant supervising the lads. – When, pray tell, may we expect the arrival of the Voivod himself? – he asked.

– The honorable Voivod is to arrive this evening. He wishes to make it to the beginning of the Sejmik.

– Is he going to stop, as per usual, in the monastery?

– Yes, my sir. He rented the inn for his people. Here, he shall prepare a feast for the participants. We have been bringing the food and the drinks in since yesterday.

– I see the Voivod is very generous when it comes to winning supporters in the sejmik. There’s going to be quite a few guests. Rumor has it that many citizens are going to show up. Everyone is very curious about the sejmik, they wish to know what proposals king will present, and whether he wishes to adopt taxes again. This will require careful consideration, and this, in turn, requires time. The previous sejmik lasted for ten days, this one will probably be even longer. Let me know, please, when the Voivod arrives. I have a great many affairs to discuss with him. We need to ponder the choice of the deputy for the Sejm of Warsaw.

– Certainly, o honorable Starost. When my lord arrives, I shall send a boy to notify you – said the Voivod’s trusted man. When the Starost was slowly walking away, another group of riders went through the town. Forty identically‑dressed men on the backs of magnificent horses rode in front of another nobleman’s carriage. The town became ever louder and more crowded. The sejmik was to take place the next day.

Mark the sentences that are true.

- A sejmik lasted one day at most.

- Many people arrived in the town.

- The sejmik elected Sejm Deputies.

- The nobility expected discussion of taxes.

- A sejmik, or a gathering of the nobility, was to take place in the town.

Show which sentences are true, and which are false.

{true}The nobility was the name used to describe the descendants of the knights.{/true}

{false}Sejm sessions took place in Warsaw only.{/false}

{true}The nobles enjoyed the same rights notwithstanding their wealth or social standing.{/true}

{true}The privilege of Czerwińsk guaranteed the nobles the inviolability of their wealth, unless it was lifted by a court ruling.{/true}

{false}The liberum veto was a principle that permitted breaks in Sejm sessions to establish a common opinion.{/false}

{true}Only the nobility enjoyed political rights in Poland.{/true}

{false}Only bishops and cardinals were members of the Senate.{/false}

{true}The gatherings of the nobility of a given region were called “sejmiks”.{/true}

{false}The Deputy Marshal directed the works of the sejmiks.{/false}

{false}The three Houses of the general Sejm were: the King, the magnates, and the nobility.{/false}

Keywords

nobility, noble privileges, liberum veto, general Sejm, Nobles’ Democracy

Glossary

Przywilej – prawa nadawane szlachcie przez polskich władców od XIII do XVI wieku.

Pospolite ruszenie – powołanie pod broń całej zdolnej do walki ludności męskiej lub jej uprawnionej części. Członkowie pospolitego ruszenia sami musieli dbać o swoje uzbrojenie i ponosić za nie koszty. W Rzeczypospolitej podlegało ono rozkazom króla.

Sejmik ziemski – lokalne zgromadzenie zwoływane w Polsce od XIV wieku w każdym województwie. Zajmował się sprawami administracyjnymi i prawem.

Sejm walny – nazwa najwyższego organu przedstawicielskiego – parlamentu – najpierw w Królestwie Polskim, a od 1569 roku w Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów, decydujące o ważnych sprawach w państwie. Składał się z dwóch izb – senatu i izby poselskiej oraz trzech stanów sejmujących króla, posłów i senatorów.

Demokracja szlachecka – panujący na ziemiach polskich system polityczny, gwarantujący stanowi szlacheckiemu prawo głosowania i decydowania o sprawach państwa. Był przykładem równości praw w stanie szlacheckim bez względu na pochodzenie, majątek czy zasługi szlachcica.

Liberum veto – zasada panujące na sejmach w dawnej Rzeczypospolitej dająca prawo zrywania i unieważniana podjętych na nich uchwał każdemu posłowi – przedstawicielowi szlachty.

Żupan – reprezentacyjna, często bogato zdobiona męska, długa szata wierzchnia. Popularna wśród polskiej szlachty w XVI i XVII wieku.

Szabla – jeden z rodzajów długiej broni siecznej. W Polsce pojawił się za panowania Stefana Batorego w XVI wieku.

Rokosz – bunt szlachty, jej zbrojne powstanie przeciwko królowi‑elektowi.

Konfederacja – w Rzeczypospolitej szlacheckiej związek szlachty, duchowieństwa lub miast mający na celu realizację określonych zadań politycznych lub obrony swoich interesów. Zwoływana była przez szlachtę m.in. w celu poparcia poczynań króla.

Szlachta – wyższy ze stanów społecznych wykształcony w XIV‑XV w. Przynależność do niej określało urodzenie i posiadanie nazwiska rodowego. Posiadała szereg przywilejów i łączyła się z obowiązkiem służby wojskowej.

Senat – w dawnej Rzeczypospolitej wyższa izba sejmu w skład której wchodzili ministrowie, wojewodowie, kasztelanowie i wyższe duchowieństwo.

Kontusz – rodzaj płaszcza lub kamizelki z rozciętymi od pachy do łokci rękawami.