The Crisis and Collapse of the Roman Empire

to define the causes of the crisis of the Roman EmpireEmpire in the third century CE;

telling who was Diocletian and what he did to end the crisis;

to describe when was the Roman Empire divided into the East and West Empires;

to define what was the Migration PeriodMigration Period and how did it influence the collapse of the Western Roman Empire;

to define at what point in history the Antiquity ended and the Middle Ages started.

The period of “Roman Peace”, ushered in by Emperor Augustus, brought the Empire peace and prosperity. Halfway through the second century CE the Roman Empire reached the peak of its power and greatness. The provincesprovinces thrived, undergoing the process of romanization, i.e. the spread of Roman models and customs. It was, however, not an easy task to maintain peace and power in such a large area. In order to keep the borders safe, the construction of the border fortification system, known as the limeslimes was undertaken. Its most widely‑known portion – the over 120 kilometer‑long Hadrian’s Wall – is still present in Britain. That notwithstanding, the Empire was facing ever greater inner problems. Especially in the third century, the state’s wellbeing was marred by numerous civil wars, usurpations, and an economic crisis. The situation was exacerbated by power struggles, joined by the legion commanders and the Praetorian Guard ever more often. Those problems resulted in the need to make changes that would restore Rome’s might.

Relative peace was brought by the rule of the Emperor Diocletian at the turn of the third century. Despite his absolutist ambitions (the Emperor demanded, for example, to be worshipped as a god) he was well aware that such a large area could not be efficiently ruled by one person. A move that was meant to save Rome was the introduction of a new system of rule – the collaborative rule of four Emperors – two of them of the superior rank of Augustus, and two of the inferior rank – the Caesars. This system was called tetrarchytetrarchy. Every ruler oversaw a different part of the Empire, and it was established that the Emperors of the superior rank would pass their power onto the Caesars after 20 years, and those would in turn choose their successors. The military power of the Empire was increased as well by increasing the legions’ numbers, strengthening the borders, fortifying the cities and enacting fiscal and administrative reform. That notwithstanding, the city of Rome lost its significance, especially when in 330 CE the Emperor Constantine the Great founded the opulent city named after himself – Constantinople. It quickly became the main capital of the Empire, heralding its looming division. The empire was divided in 395 CE, in accordance with the will of Theodosius the Great – at the moment of his death. The Roman Empire became permanently divided into the Western Empire with its capital in Ravenna, and the Eastern Empire with its capital in Constantinople.

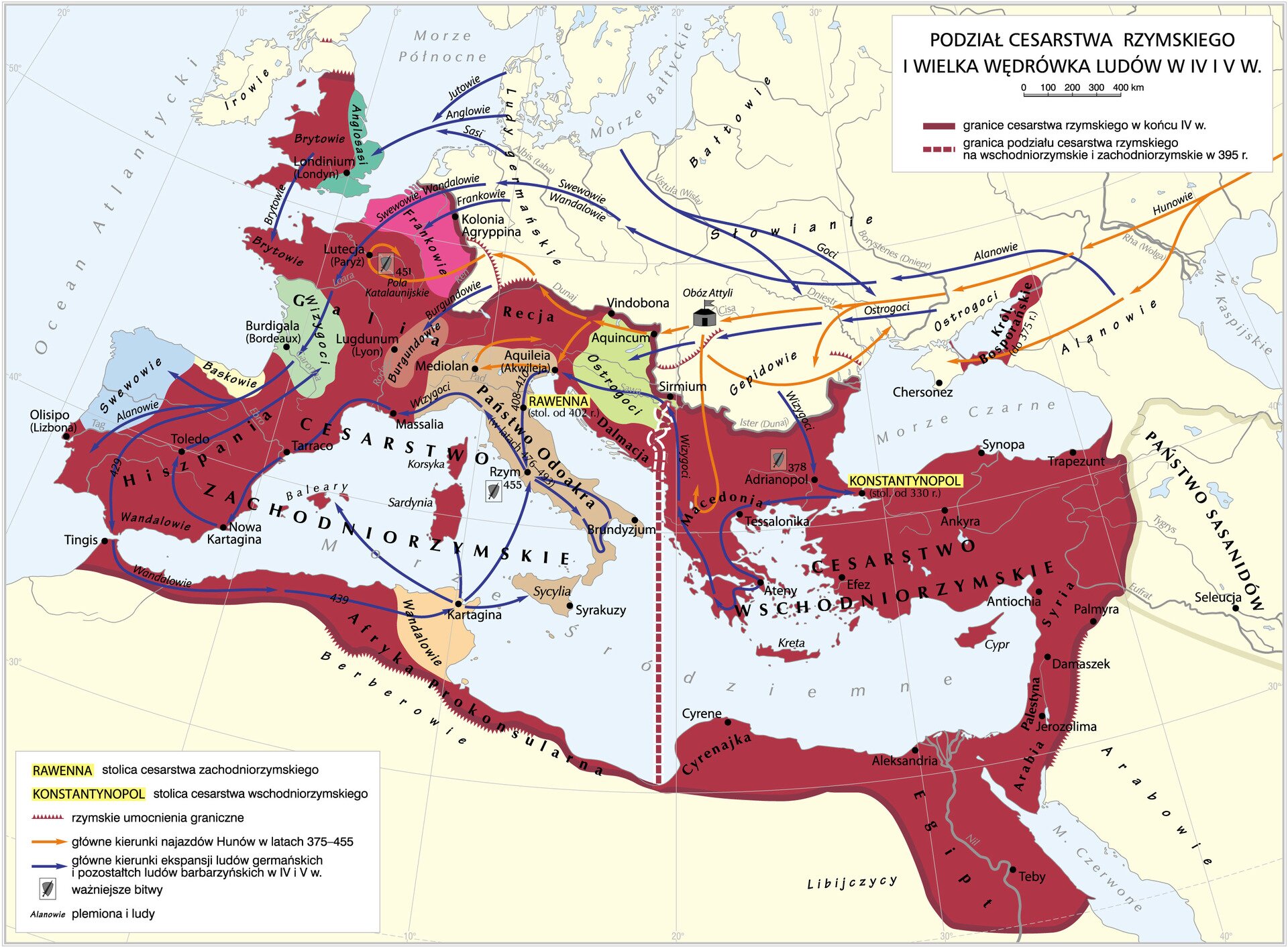

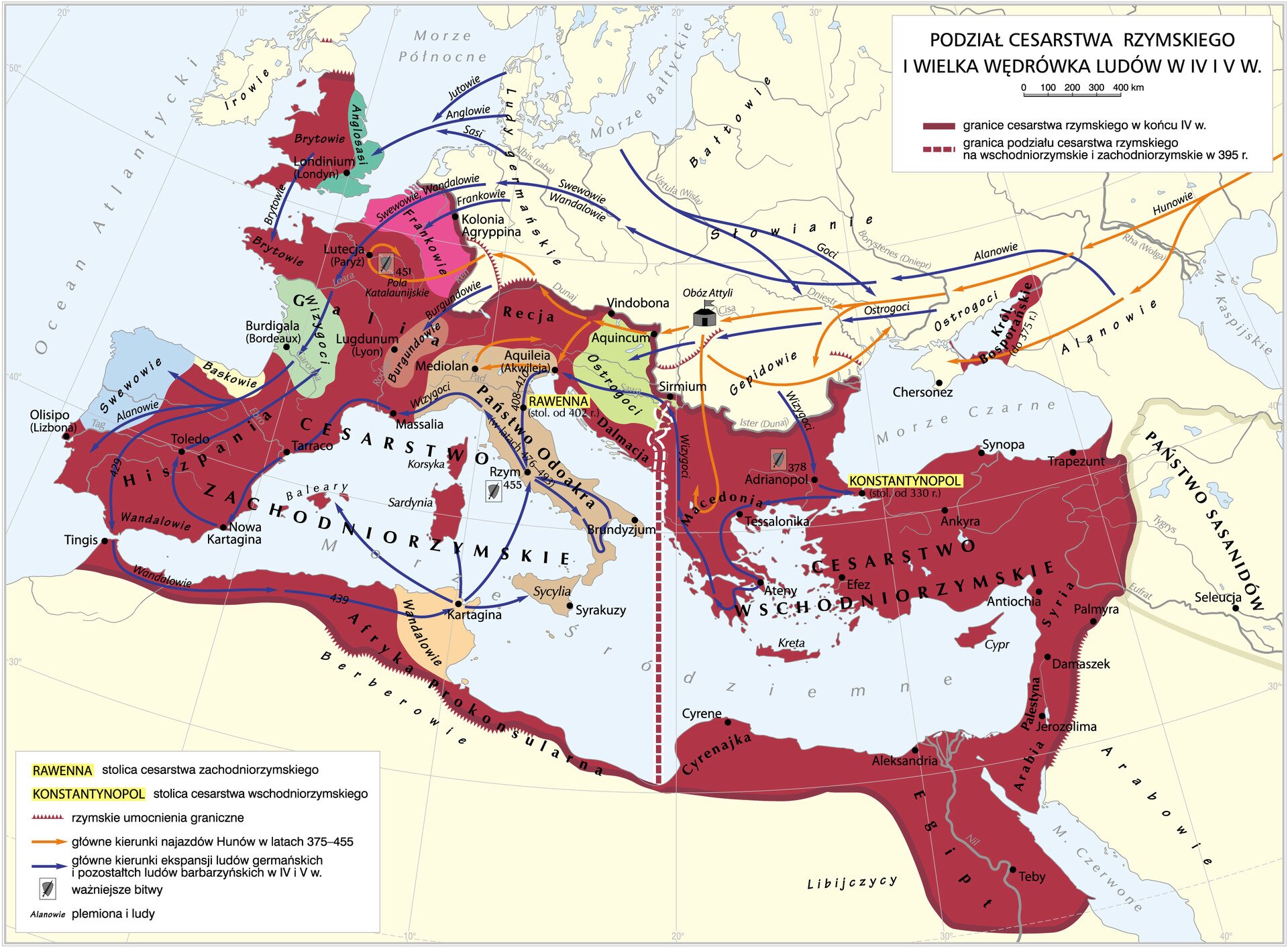

By the end of the fourth century, the Empire experienced a period of mass migration, later known as the Migration Period. The Empire’s borders started experiencing an influx of numerous barbaric peoples. The Germanic Visigoths entered the area of Italy, sacking and burning the city of Rome in 410 CE. Subsequent Germanic tribes settled in Gaul and Spain (initially as allies), the Vandals seized part of North Africa. This led to the loss of control of the emperors over the key provinces of the Roman Empire. Unfortunately, the Empire’s worst moments were only yet to come. At the beginning of the fifth century Attila, the ruler of the Asian Huns, together with the tribes subject to him, attacked Gaul. In the great battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451, he was stopped by the united forces of Roman Gaul and the barbarians inhabiting the Empire’s territory. The peace, however, did not last long, and Rome was still threatened by the Vandals, who, led by Genseric, sacked the city again in 455. Since then, the power in the Western Empire was effectively held by the Germanic leaders, which in turn led to the deposition of the young Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, in 476. This event is considered the final collapse of the Western Roman Empire and became the point in history that marked the end of Antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

When Gaul experienced disorder at the hands of peasants and bandits, i.e. the so-called bagaudae, who looted the country and began to harass the cities, Diocletian named a dear friend of his, Maximian, a man of modest education, yet a good and skilled soldier, Emperor. Revered as a god afterwards, Maximian assumed the sobriquet of “Herculius”, similar to how Diocletian assumed that of “Jovius” [...]. Since their contemporaries, the Persians, harassed the Eastern provinces cruelly, and Africa was being raided by the Mauretanian tribes, with Egypt experiencing the rise of a new usurper, he selected helpers called the Caesars: Constantius and Galerius, and united them with himself by way of affinity. After having ended their previous marriages, the former received the stepdaughter of Heraclius, and the latter – the daughter of Diocletian. Their motherland was Illiricum, and despite their modest education, they were well-versed in the tough conditions of the military and countryside life, rendering them perfect rulers of the country. [...] as the numerous wars put a strain on the state, they divided it into four parts, and thus Constantius received the area of Gaul past the Alps, Herculius took Africa and Italy, Galerius got the Illiricum all the way until the Pontine Strait, and the rest (i.e. the East) was taken by Diocletian himself. [...] Source: Aureliusz Wiktor, O cezarach [in:] S. Sprawski, G. Chomicki, Starożytność. Teksty źródłowe, komentarze i zagadnienia do historii w szkole średniej , Kraków 1999, s. 273-274.

In the text, mark the changes introduced by Diocletian in the system of rule, as well as their causes:

causes of changes introduced changes

Valerius Diocletian [...] was an exceptional man, though not without vices. He was the first to introduce the exquisite, purple silk robes woven with gold thread, and shoes studded with precious gems. He was the first Emperor since Caligula and Domitian to demand to be called lord and god, as well as divine honors during greetings. [...] Those vices seemed, however, to be outweighed by his virtues; even though he demanded to be called lord, he was the father of his subjects [...].

When Gaul experienced disorder at the hands of peasants and bandits, i.e. the so-called bagaudae, who looted the country and began to harass the cities, Diocletian named a dear friend of his, Maximian, a man of modest education, yet a good and skilled soldier, Emperor. Revered as a god afterwards, Maximian assumed the sobriquet of “Herculius”, similar to how Diocletian assumed that of “Jovius” [...]. Since their contemporaries, the Persians, harassed the Eastern provinces cruelly, and Africa was being raided by the Mauretanian tribes, with Egypt experiencing the rise of a new usurper, he selected helpers called the Caesars: Constantius and Galerius, and united them with himself by way of affinity. After having ended their previous marriages, the former received the stepdaughter of Heraclius, and the latter – the daughter of Diocletian. Their motherland was Illiricum, and despite their modest education, they were well-versed in the tough conditions of the military and countryside life, rendering them perfect rulers of the country. [...] as the numerous wars put a strain on the state, they divided it into four parts, and thus Constantius received the area of Gaul past the Alps, Herculius took Africa and Italy, Galerius got the Illiricum all the way until the Pontine Strait, and the rest (i.e. the East) was taken by Diocletian himself. [...]

Source: Aureliusz Wiktor, O cezarach [in:] S. Sprawski, G. Chomicki, Starożytność. Teksty źródłowe, komentarze i zagadnienia do historii w szkole średniej , Kraków 1999, s. 273-274.

Using the map as reference, match the provinces to the tetrarch they were ruled by.

Britain, Asia, Thrace, Moesia, Gaul, Italy, Hispania, Egypt

| Diocletian | |

|---|---|

| Galerius | |

| Maximian | |

| Constantius |

Mark the reforms thanks to which the crisis of the third century ended.

- The introduction of tetrarchy.

- Agrarian reform.

- Tax reform.

- Abolition of the Senate.

- Declaring war on the barbarians.

- Administrative reform.

Indicate the Emperor that divided the Empire.

- Theodosius the Great

- Augustus

- Constantine the Great

- Diocletian

Indicate the year that marked the division of the Roman Empire into the Eastern and Western Empires.

- 395.

- 378.

- 330.

- 386.

Read the timeline and explain how the collapse of the Roman Empire happened.

Using the map and the knowledge obtained in class as reference, fill in the gaps.

tetrarchy, Vandals, Huns, Western, Antiquity, Odoacer, 395, reforms, Diocletian, Migration Period, Constantinople, crisis, Eastern

In the third century, the Roman Empire found itself in ................................. For some time the Emperor, ................................, brought a stop to the state’s difficulties by enacting numerous ................................. He also introduced ................................, or the system of collaborative rule of four emperors, each of whom was responsible for a different part of the empire. In the fourth century, the raids of the barbaric tribes launched the ................................. The ................................ ravaged Gaul and Hispania, then settled in North Africa. The ................................ came to Europe from Middle Asia, attacking the northern provinces of the Empire. The barbarians’ attacks led to the division of the state in ................................ into the ................................ Empire with its capital in Ravenna and the ................................ Empire with its capital in ................................. In 476 the Germanic leader ................................ sacked Rome and deposed the last Emperor, Romulus Augustulus. This date has been assumed as the turning point that marked the end of .................................

Keywords

Cesarstwo, Tetrarchia, Prowincja

Glossary

Uzurpator – władca, który w bezprawny i samowolny sposób zagarnął pełnię władzy lub prawa do niej.

Cesarstwo – forma ustroju państwa – monarchii – w której panujący obdarzony jest tytułem cezara. Cesarstwo rzymskie zostało zapoczątkowane przez Oktawiana Augusta.

Pryncypat – forma rządów w Cesarstwie Rzymskim wprowadzona przez Oktawiana Augusta, polegająca na koncentracji władzy w rękach jednej osoby przy zachowaniu pozorów ustroju republiki.

Tetrarchia – dosłownie rządy czterech, wprowadzony przez cesarza Dioklecjana system rządów polegający na równoczesnym panowaniu czterech władców – dwóch wyższej rangi – augustów oraz dwóch niższej – cezarów.

Wielka wędrówka ludów – migracja plemion barbarzyńskich na tereny Cesarstwa Rzymskiego w okresie od IV do VI w. Doprowadziła do licznych zmian etnicznych w Europie przyczyniając się do upadku cesarstwa zachodniorzymskiego.

Prowincja – jednostka administracyjna w starożytnym Rzymie utworzona na podbitym terenie, poza Italią. Zarządzana była przez namiestników.

Limes – umocnienia i fortyfikacje na granicach cesarstwa rzymskiego.