The Era of Crusades

what was the history of Palestine;

who threatened the Byzantine Empire and the pilgrims to the Holy Land;

how was the crusade movement born;

why did the chivalric orders come into being and what was their role.

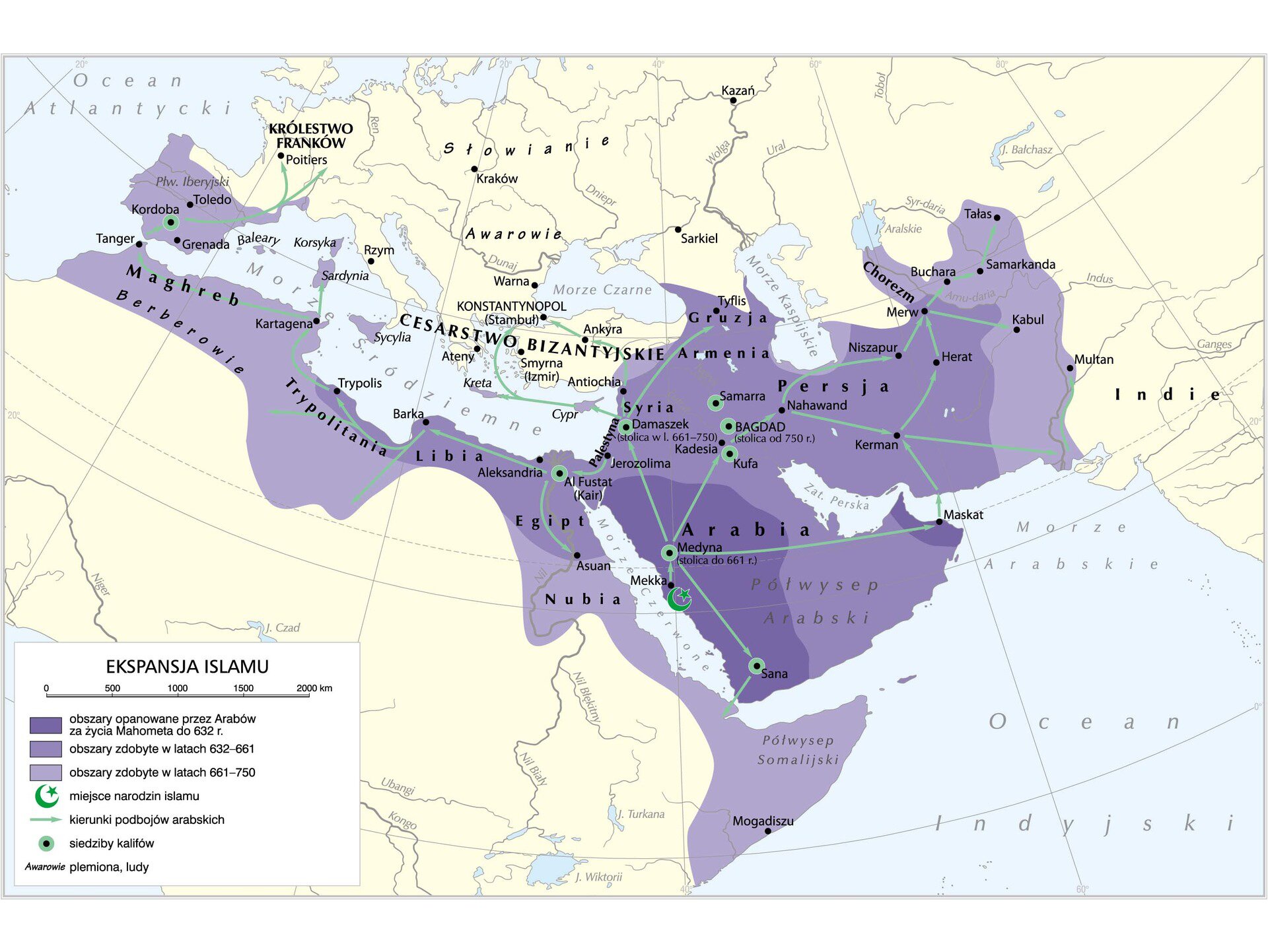

Ever since the beginning of Christianity, the Holy Land was an unique place to the believers. Pilgrimages to the holy sites took place as early as in the first centuries of Christianity, but, unfortunately, ever since the Arabs conquered those territories in the seventh century, this movement was put to an end. It was reborn only three centuries later, when the CaliphCaliphate of Egypt was taken over by the Musilm dynasty of Fatimids that maintained friendly relations with Constantinople and was exhibited tolerance for Christians. The situation underwent a drastical change in the middle of the eleventh century, when the Asian portion of the former Arab Empire was taken over by the Seljuq Turks, who subdued the Baghdad CaliphCaliphate. Their policy on Christians was completely different from that of their predecessors. It became one of the reasons for the beginning of the CrusadesCrusades, whose aim was to retake the holy sites from the Muslims.

During the synod of Clermont in 1095, the Pope called for every Christian in Western Europe to fulfill the duty of defending Christianity, provide support to the Byzantine Empire against the Turkish threat, and liberate the holy sites in Palestine from the hands of the Muslims. In 1096, masses of people answered the Pope’s call and marched through Europe. The People’s CrusadeCrusade, as it was called, could have involved as much as 200 thousand people, according to some researchers. However, the crowd, unprepared and lacking the support of the knights, was easily defeated by the Turkish military in Anatolia.

In the same year, the first knights’ Crusade, known as the Princes’ Crusade, was organized. As many as 60 thousand knights, coming mainly from the Romance‑language countries, took part in it. It was headed by many notable magnates, such as Raymond of Toulouse, Godfrey of Bouillon, and Hugo, Count of Vermandois and son of the King of France. During the First Crusade, they not only defeated the Turks in Asia Minor, but also gained numerous territories from Syria and Palestine to Sinai, recapturing Jerusalem in 1099. The idea of chivalric orders was born, three of which – the Templars, the Joannites, and the Teutonic Order – came into being in Palestine. Despite their initial success, the Crusaders did not manage to keep the conquered territories for long. The incessant Muslim attacks led to the fall of the first Christian state on those territories – the County of Edessa (1144). The subsequent CrusadeCrusade called in order to reclaim them, led by Conrad III of Germany and Louis VII of France, was unsuccessful. It only reinforced the Byzantines’ negative attitudes towards Crusaders, leading to tragic consequences – the Crusaders looted Constantinople in 1204. The new state established on its territory that was meant to reuinte the divided Christian community, the Latin Empire, not only failed to achieve its goals, but also furthered the Byzantine citizens’ aversion towards the Catholics. After numerous clashes and Byzantine raids, the Latin Empire fell a few decades later in 1261.

In the second half of the twelfth century, SultanSultan Saladin became the leader of the Muslims, uniting the Arabs and Turks and leading them to victory over the Christian armies in the Battle of Hattin in 1187. He conquered nearly the whole Kingdom of Jerusalem. In response, the Third CrusadeCrusade was called in Europe, a joint endeavor by the rulers of France, England, and the German Reich. It was, however, unsuccessful and did not manage to recapture Jerusalem or defeat Saladin’s armies. The next expeditions only delayed the final loss. It happened with the fall of the last Christian stronghold – Acre – in 1291.

Study the maps of the expansion of Islam and the division of the world into the Christian and Muslim spheres.

Read the source text and complete the exercise.

Historia Hierosolymitana[...] wasi bracia, którzy znajdują się na Wschodzie, bardzo potrzebują waszej pomocy. I musicie się śpieszyć, żeby udzielić im pomocy, o którą tak często, bez skutku, zabiegali. Bo, jak pewnie większość z was słyszała, zaatakowali ich i podbili [ich ziemie] aż do wybrzeża Morza Śródziemnego i Hellespontu [tj. cieśnin i morza Marmara oddzielających Azję Mniejszą od Europy] Turcy, lud perski [i Arabowie], którzy coraz więcej i więcej zajmowali ziem chrześcijan u granic Bizancjum. Pobili ich [wschodnich chrześcijan] w siedmiu bitwach. Zabili i pojmali wielu, obrabowali kościoły i spustoszyli królestwo Boże. Jeśli pozwolicie im kontynuować to [tj. zniszczenie Bizancjum] bezkarnie, wierni Bogu będą jeszcze mocniej atakowani. Z tego względu ja, lub raczej Pan, zobowiązuję was jako heroldów Chrystusa, by głosić to wszędzie i zachęcać ludzi wszelkiego stanu i rangi, rycerzy i wojów pieszych, bogatych i biednych, by nieśli szybko pomoc tym chrześcijanom i usunęli tę rasę [tj. Turków i Arabów ] z ziem naszych przyjaciół. [...] Tak nakazuje Chrystus.

Source: Fulcher z Chartres, Historia Hierosolymitana, oprac. H. Hagenmeyer, tłum. Heidelberg, P. Wiszewski, 1913, s. 132.

What goals did the Pope set before the Western knights? Answer by marking the correct ending of the sentence.

- conquering Egypt.

- helping the Byzantines.

- destroying all of the Muslim states.

Study the interactive illustration and learn more about the Christian and Muslim armies fighting in the Holy Land.

Read the account of Fulcher of Chartres, then complete the exercise.

The Crusades came from Europe – the knights, their servants, merchants, clergymen – they created a new society in the Middle East. The Latins, as they are called by historians, were a group consisting of all of the European ethnicities of the time. The group was dominated by Southern Frenchmen, but a significant number of Germans, inhabitants of Italy, and even Englishmen was also present. They all initiated contacts with the local populace rather quickly.

Fulcheri Carnotensis Historia HiersolymitanaProszę Cię, zwróć uwagę i rozważ, jak Bóg w naszych czasach przekształcił Zachód we Wschód. Bowiem my, mieszkańcy Zachodu, zostaliśmy uczynieni mieszkańcami Wschodu. Ten, kto był Rzymianinem lub Frankiem, teraz z racji zamieszkania jest Galileańczykiem lub Palestyńczykiem. [...] Zapomnieliśmy już miejsca naszych urodzin, są już nieznane dla wielu z nas, a przynajmniej się o nich nie mówi. Niektórzy posiadają tu dom i służbę, które otrzymali jakby na prawie dziedziczenia. Niektórzy wzięli sobie żony nie ze swojego ludu, ale Syryjki, Ormianki, a nawet Saracenki, które zostały ochrzczone. Niektórzy mają wraz z nimi teścia, szwagra, synową lub zięcia, przybranego syna lub ojczyma. Są tutaj również wnukowie i prawnukowie [tych, którzy przybyli na Wschód, tutaj urodzeni]. Jeden uprawia winnice, inny pola. Jeden i drugi używają nawzajem języka ze słowami z różnych języków. Różne języki, teraz powszechne, stają się znane obu społecznościom [Zachodu i Wschodu] i wiara jednoczy tych, którzy są sobie obcy pochodzeniem. [...].

Source: Fulcheri Carnotensis Historia Hiersolymitana, t. III,37,2---5, tłum. P. Wiszewski, s. 748.

Fill the table by matching the given phenomenon to the appropriate quote.

they form mixed marriages., they must speak a new language formed by the fusion of their old tongues, or use many different ones at a time., they became rich and formed economic bonds with their new home., they left behind the memory of Europe as their place of origin, attaching themselves and their families to the East.

| The Latins are forming a new society, because: | Words of the chronicler |

|---|---|

| they form mixed marriages. | |

| they must speak a new language formed by the fusion of their old tongues, or use many different ones at a time. | |

| they became rich and formed economic bonds with their new home. | |

| they left behind the memory of Europe as their place of origin, attaching themselves and their families to the East. |

Among the possibilities listed below, indicate the effects of the Crusades.

- Birth of chivalric orders

- Development of trade with India

- Rise of papal authority

- Translating the Holy Bible into the national languages

- Temporary establishment of Christian states in Holy Land

- Reunion of the Churches of the East and the West

- Strengthening of the resentment between Eastern and Western Christians

- Development of the sacerdotal education system

- Contact of the Western Europeans with the works and heritage of Antiquity through the Arabs and the Byzantines

- Religious tolerance

- Appearance of oriental influences in art

Keywords:

crusade, chivalric order, reconquista, Latin, christianization, caliph, emir, saracens, pagans

Glossary

Krucjaty – średniowieczne wypraw zbrojne ogłaszane najczęściej przez papieży i prowadzone przeciwko innowiercom (muzułmanom, heretykom, ale i katolikom) oraz poganom. Ich głównym celem miała być obrona miejsc świętych i chrystianizacja.

Poganie – określenie stosowane przez chrześcijan wobec wyznawców innych religii i wierzeń. Określnie to od zawsze miało charakter obelgi i oznaczało osobę gorszą, mniej znaczącą.

Chrystianizacja – proces przyjmowania symboli i wiary chrześcijańskiej oraz zastępowanie nią wierzeń pogańskich.

Kalif – tytuł następców Mahometa, będących przywódcami religijnymi i państwowymi muzułmanów.

Emir – w państwie arabskim zarządca prowincji powoływany przez kalifa.

Sułtan – tytuł władcy używany w wielu państwach muzułmańskich. Początkowo oznaczał głównodowodzącego całym wojskiem kalifa.

Rekonkwista – termin określający walkę chrześcijan z muzułmanami (między VIII‑XV w.) zamieszkującymi Półwysep Iberyjski, której celem było odzyskanie ziem spod ich panowania.

Łacinnicy – określenie zachodnich chrześcijan (katolików) przybywających i zamieszkujących tereny królestw chrześcijańskich na Bliskim Wschodzie.