Przeczytaj

Scientists of various specialisations do research in order to understand the connections between material situation and health. These kinds of studies require long‑term observations of entire populations as doctors try to look into the impact of deprived upbringing on the development of heart diseases later in life. In the case of developing countries, the challenge is twofold. First of all, there are many existing medical problems to tackle. Secondly, it’s of the essence to help those nations avoid diseases of affluence, which inevitably follow the economic growth and changes in the lifestyle of citizens.

Naukowcy wielu specjalizacji prowadzą badania w celu zrozumienia związków pomiędzy statusem materialnym i stanem zdrowia. Takie badania wymagają długoletnich obserwacji całych populacji. Lekarze starają się dociec, czy istnieje związek między wychowaniem w niedostatku i rozwojem chorób serca w późniejszym wieku. W przypadku krajów rozwijających się wyzwanie jest podwójne. Po pierwsze, rozwijające się społeczeństwa potrzebują pomocy w rozwiązaniu aktualnych problemów natury medycznej. Po drugie, wymagają również wsparcia, aby zapobiegać chorobom cywilizacyjnym, które idą w parze ze wzrostem gospodarczym i zmianami trybu życia.

Read the text and do the exercises below.

The Poverty Disease or Diseases of Poverty?It might be hard to believe but 45.8 percent of global household wealthglobal household wealth is in the hands of just 1.1 percent of the world's population. According to another indexindex, 50% of people on Earth live for less than $2 per day. What’s even more shocking, the poverty indexpoverty index has been growing exponentiallygrowing exponentially in countries such as the USA, which we tend to perceive as a land of opportunityland of opportunity and traditionally associate with affluent lifeaffluent life.

Scientists seem to be in agreement regarding the relationship between health and material situationmaterial situation. They claim that chronic diseaseschronic diseases are largely diseases of deprived communitiesdeprived communities, no matter where in the world they live. Long‑term studiesLong‑term studies carried out in Glasgow clearly show that people living in poorer areas of the city die 20 years earlier than those inhabiting more affluent districts. The causes of death are often cardio‑vascular diseasescardio‑vascular diseases. We cannot generalise, but education seems to play an important role here. People from run‑down districtsrun‑down districts with limited access to education seem to have lower awareness of the effect of their artery‑clogging dietsartery‑clogging diets and unhealthy lifestyles on their health. UntreatedUntreated, resulting diseases prove fatalprove fatal much earlier than in other communities.

Poverty affects how quickly and easily people can receive medical assistancemedical assistance, however, there are different dimensions in terms of access to healthcareaccess to healthcare. There are regions of the world, where people live in such remote or deprived areas, that any more serious medical conditionmedical condition may turn out to be lethallethal. On the other hand, there are highly developed countries which, however, require their citizens to pay costly medical insurancecostly medical insurance. The result is that although healthcare may be at a really high level, people living in poverty cannot afford medical supportcannot afford medical support. Not having access to primary careprimary care often leads to people developing conditions which are later much more difficult and costly to treat.

Some people say that poverty itself is a disease. A person born into an impoverished areaimpoverished area or family is likely to repeat the same patterns of behaviourrepeat the same patterns of behaviour. They more often reach for drugs and alcohol because they see the older generation do the same. Growing up in poverty has been proven to affect people’s chances of social mobilitysocial mobility. Children from deprived areas are often labelled no‑hopersno‑hopers, they don’t believe in their abilities and they end up living off social security benefitsliving off social security benefits rather than trying to make their own livingmake their own living. What’s more, scientists have gathered enough data to draw preliminary conclusionsdraw preliminary conclusions about the impact of distress and the lack of life prospectslack of life prospects early on on the likelihood of the development of heart diseases later in life. Apparently, people who have experienced deprived childhoodsdeprived childhoods have higher levels of inflammationinflammation in their bodies and these lead to various cardio‑vascular diseases.

Poverty, however, is not only connected with heart diseases. It affects people’s mental healthmental health heavily. Wherever there is a change in socio‑economic patternschange in socio‑economic patterns in society resulting from a long‑lasting financial crisislong‑lasting financial crisis, we observe an increase in the number of people seeking mental health support. Prolonged unemploymentProlonged unemployment, impossibilismimpossibilism, hopelessnesshopelessness that anything will ever change impacts people’s psychic heavily and can trigger diseasestrigger diseases both physical and mental.

Last but not least, the relationship between poverty and ill‑healthill‑health works both ways. Through reasons mentioned above, poverty contributes to disease but also ill‑health can lead to poverty. When people fall ill, they lose the ability to generate incomegenerate income and find themselves on a slippery slope to povertyslippery slope to poverty. In the long run, it impacts the whole community or even country. Children cannot learn, adults cannot work, families lose their breadwinnersbreadwinners. If in some places the disease burdendisease burden is big, it can push the whole area or even state into poverty. It’s important to understand those interdependenciesinterdependencies to be able to support people on their way to break the poverty trapbreak the poverty trap.

Źródło: Anna Posyniak‑Dutka, licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0.

TrueFalse

2. Only in some parts of the world do people suffer from chronic diseases caused by poverty.

TrueFalse

3. People who do not realise that there is a link between their harmful lifestyles and their health increase their chances of dying from certain diseases.

TrueFalse

4. In places far from the centres with healthcare facilities, people are more likely to develop diseases that could otherwise be treated.

TrueFalse

5. People in rich countries more often develop diseases which are costly to treat.

TrueFalse

6. People born and raised in poverty are more likely to be poor in the future.

TrueFalse

7. Being exposed to poverty early in life increases people’s vulnerability to heart conditions later in life.

TrueFalse

8. A growing number of mental health conditions alter socio-economic patterns in society.

TrueFalse

9. People who suffer from poor health often slip and break bones.

TrueFalse

10. Widespread diseases make whole societies poor.

TrueFalse

2. a kind of lifestyle when people have all they need or even more | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

3. illnesses which last for a long time, sometimes for life | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

4. groups of people who suffer from lack of shortages of basic necessities | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

5. the kind of food and drink the consumption of which results in the person’s blood vessels being blocked | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

6. people who nobody believes will ever succeed in achieving anything | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

7. the ability to elevate oneself from one level of society to another | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

8. money paid by governments to people who cannot support themselves | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

9. early years in the life of a person which are spent in a state of lack or shortages of basic necessities | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

10. to earn money | 1. chronic diseases, 2. deprived communities, 3. no-hopers, 4. affluent life, 5. social security benefits, 6. artery-clogging diet, 7. deprived childhood, 8. poverty index, 9. social mobility, 10. generate income

Answer the question. How may living in an impoverished area affect people’s life? Write 5–6 sentences.

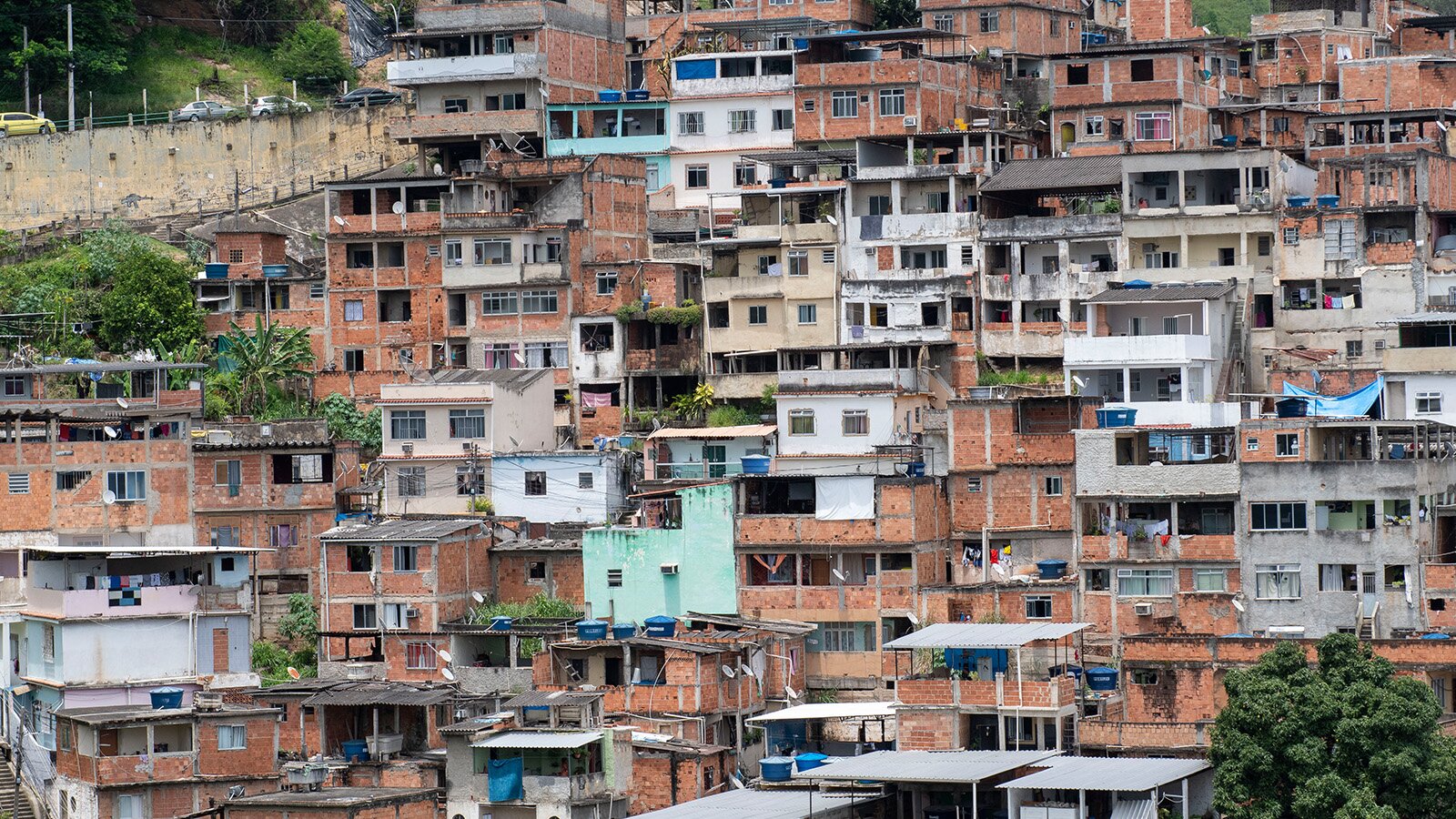

Look at the picture below. What kind of place is it? How may living in such a place affect people’s life? Write 5‑6 sentences.

Słownik

/ ˈækses tu ˈhelthetaˌker /

dostęp do służby zdrowia (possibility to use medical services)

/ ˈæfluənt lʌɪf /

dostatnie życie (lifestyle characterised by access to large sums of money)

/ ˈɑːtəri ˈklɒɡɪŋ ˈdaɪəts / / ˈɑːtəri ˈklɒɡɪŋ ˈdaɪət /

diety prowadzące do zatykania arterii [dieta prowadząca do zatykania arterii] (kind of nutrition which results in arteries being blocked)

/ ˈbredwɪnəz / / ˈbredwɪnə /

żywiciele rodziny [żywiciel/żywicielka rodziny] (a person who earns money to provide for the family)

/ ˈbreɪk ðə ˈpɒvəti træp /

wydostać się z pułapki biedy (to manage to get out of the situation of being extremely poor)

/ ˈkænɒt əˈfɔːd ˈmedɪkl̩ səˈpɔːt /

nie mogą sobie pozwolić na pomoc medyczną (to not have enough financial means to pay for healthcare)

/ ˌkɑːdiəʊˈvæskjələ dɪˈziːzɪz / / ˌkɑːdiəʊˈvæskjələ dɪˈziːz /

choroby sercowo‑naczyniowe [choroba sercowo‑naczyniowa] (a disease affecting the heart and/or circulatory system)

/ tʃeɪndʒ ɪn ˈsosiəʊ ˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk ˈpætn̩z / / tʃeɪndʒ ɪn ə ˈsosiəʊ ˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk ˈpætn̩ /

zmiana w układach społeczno‑gospodarczych [zmiana w układzie społeczno‑gospodarczym] (an alteration in the way social and economic relations function)

/ ˈkrɒnɪk dɪˈziːzɪz / / ˈkrɒnɪk dɪˈziːz /

choroby przewlekłe [choroba przewlekła] (a medical condition which continues for a long time)

/ ˈkɒstli ˈmedɪkl̩ ɪnˈʃʊərəns /

drogie ubezpieczenie medyczne (high costs of contributions paid towards healthcare)

/ dɪˈpraɪvd ˈtʃaɪldhʊdz / / dɪˈpraɪvd ˈtʃaɪldhʊd /

dzieciństwa w biedzie [dzieciństwo w biedzie] (early years spent in poor conditions)

/ dɪˈpraɪvd kəˈmjuːnɪtɪz / / dɪˈpraɪvd kəˈmjuːnɪti /

ubogie społeczności [uboga społeczność] (poor communities)

/ dɪˈziːz ˈbɜːdn̩ /

obciążenie chorobą (a strain put on somebody by an illness)

/ drɔː prɪˈlɪmɪnəri kənˈkluːʒn̩z / / drɔː prɪˈlɪmɪnəri kənˈkluːʒn̩ /

wyciągnąć wstępne wnioski [wyciągnąć wstępny wniosek] (to arrive at first conclusion)

/ ˈfɒstə ˈpiːpl̩ /

wspierać ludzi (to support people)

/ ˈdʒenəreɪt ˈɪnkʌm /

zarabiać (to earn money)

/ ˈɡləʊbl̩ ˈhaʊshəʊld weltheta /

majątek gospodarstw domowych na świecie (financial means at the disposal of families across the world)

/ ˈgrəʊɪŋ ˌekspəˈnenʃəli / / ɡrəʊ ˌekspəˈnenʃəli /

rośnie wykładniczo [rosnąć wykładniczo] (to grow faster and faster)

/ ˈhəʊplɪsnəs /

desperacja, bezsensowność (lack of hope)

/ ˌɪl heltheta /

zły stan zdrowia (poor health condition)

/ɪmˈpɒsɪbɪlɪzm/

imposybilizm, bezwład (belief that nothing can be done or changed)

/ ɪmˈpɒvərɪʃt ˈeəriə /

zubożały teren (an area that used to be well‑off and now is poor)

/ ˈɪndeks /

wskaźnik (an indicator of something)

/ ˌɪnfləˈmeɪʃn̩ /

zapalenie (a state in the body caused by an infection or disease)

/ ˌɪntədɪˈpɛndənsɪz / / ˌɪntədɪˈpɛndənsɪ /

współzależności [współzależność] (a condition when two or more things depend on each other)

/ ˈlæk əv lʌɪf prəˈspekts /

brak perspektyw życiowych (no opportunities for changing one’s life situation)

/ ˈlænd əv ˌɒpəˈtjuːnɪti /

kraj/kraina możliwości (a place where many possibilities are available)

/ ˈliːthetal̩ /

śmiertelny/śmiertelna (deadly)

/ ˈlɪvɪŋ ɒf ˈsəʊʃl sɪˈkjʊərɪti ˈbenɪfɪts / / ˈlaɪv ɒf ˈsəʊʃl sɪˈkjʊərɪti ˈbenɪfɪts /

żyjąc z zasiłków opieki społecznej [żyć z zasiłków opieki społecznej] (to base one’s existence on money provided by government)

/ lɒŋ ˈlɑːstɪŋ faɪˈnænʃl̩ ˈkraɪsɪs /

długotrwały kryzys finansowy (financial recession that lasts for a long time)

/ lɒŋ tɜ:m ˈstʌdɪz / / lɒŋ tɜ:m ˈstʌdi /

długoterminowe badania [długoterminowe badanie] (observation or experiment that lasts for a long time)

/ ˈmeɪk ðeər əʊn ˈlɪvɪŋ / / ˈmeɪk jə ˈlɪvɪŋ /

samodzielnie zarobić na życie [zarabiać na życie] (to earn money to provide for oneself)

/ məˈtɪərɪəl ˌsɪtʃʊˈeɪʃn̩ /

status materialny (one’s position as determined by financial means available to that person)

/ ˈmedɪkl̩ əˈsɪstəns /

pomoc medyczna (medical support)

/ ˈmedɪkl̩ kənˈdɪʃn̩ /

choroba (disease)

/ ˈmentl̩ heltheta /

zdrowie psychiczne (psychic health)

/ nəʊˈhəʊpəz / / nəʊˈhəʊpə /

nieudacznicy [nieudacznik/nieudacznica] (a person who never succeeds in anything and nobody believes in)

/ ˈpɒvəti ˈɪndeks /

wskaźnik ubóstwa (an indicator which shows how big the scale of poverty is in a given area)

/ ˈpraɪməri keə /

podstawowa opieka medyczna (basic medical services)

/ prəˈlɒŋd ˌʌnɪmˈploɪmənt /

przedłużające się bezrobocie (a long‑lasting state of being out of job)

/ pruːv ˈfeɪtl̩ /

okazać się śmiertelną (to turn out to be deadly)

/ rɪˈpiːt ðə seɪm ˈpætn̩z əv bɪˈheɪvjə /

powtarzają te same wzorce zachowań [powtarzać te same wzorce zachowań] (to act according to the same scheme)

/ ˈrənˈdaʊn ˈdɪstrɪkts / / ˈrənˈdaʊn ˈdɪstrɪkt /

podupadłe dzielnice [podupadła dzielnica] (impoverished part of a city)

/ ˈslɪpəri sləʊp tu ˈpɒvəti /

równia pochyła do biedy (a situation which can easily result in a person becoming poor)

/ ˈsəʊʃl məʊˈbɪlɪti /

mobilność społeczna (moving up or down the social ladder)

/ ˈtrɪgə dɪˈziːzɪz / / ˈtrɪgə ə dɪˈziːz /

wywołać choroby [wywołać chorobę] (to cause an illness)

/ ʌnˈtriːtɪd /

nieleczony/nieleczona (not taken care of medically)

Źródło: GroMar Sp. z o.o., licencja: CC BY‑SA 3.0